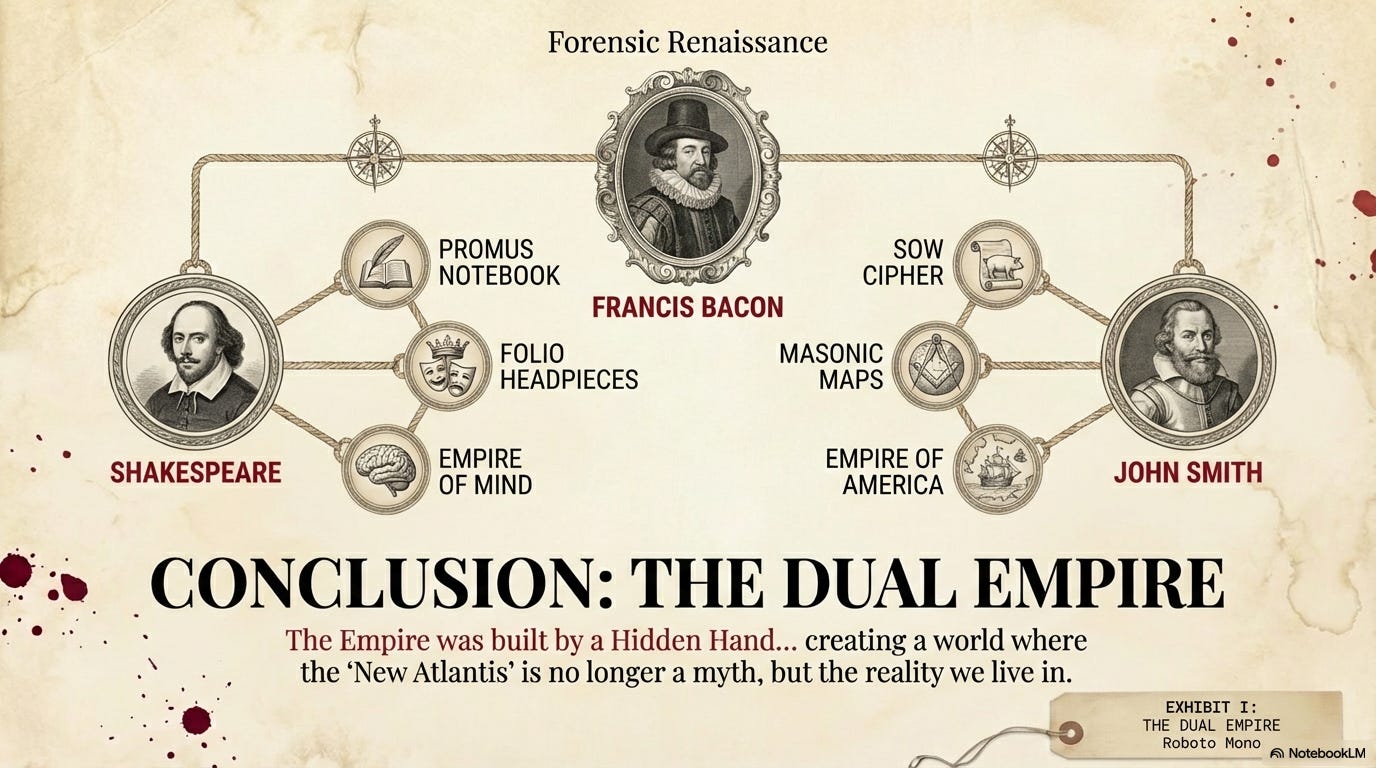

Baconian EpiWar™️

Manufacturing the Myths of William Shakespeare and John Smith

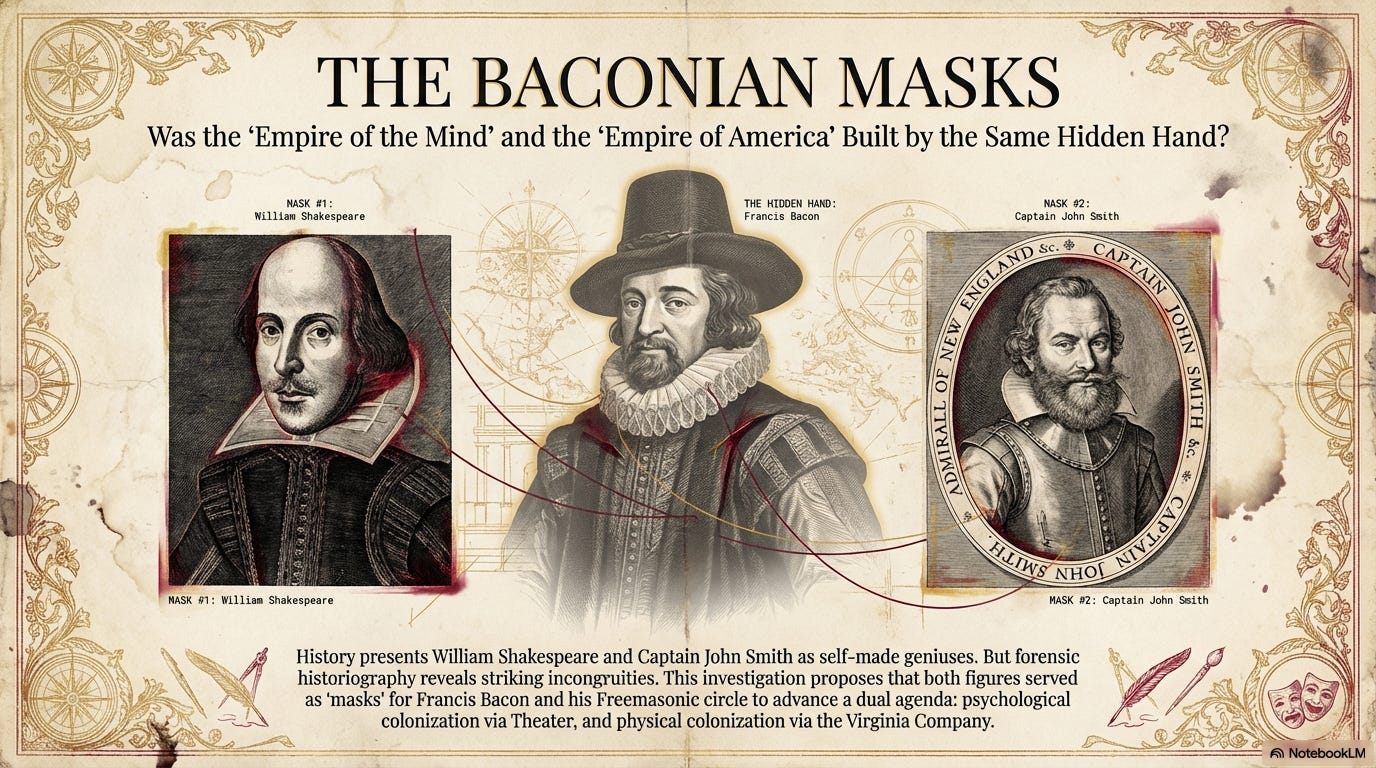

The Baconian Masks

Was the “Empire of the Mind” and the “Empire of America” Built by the Same Hidden Hand?

History presents William Shakespeare and Captain John Smith as self-made geniuses. But forensic historiography reveals striking incongruities. This investigation proposes that both figures served as “masks” for Francis Bacon and his Freemasonic circle to advance a dual agenda: psychological colonization via Theater, and physical colonization via the Virginia Company.

Part One

The “Impossible” Authors

The 17th century was a period of orchestrated psychological and territorial expansion. At the heart of this expansion was the strategic use of “masks” — public-facing surrogates that concealed the activities of a central intellectual cabal. These figures enabled a hidden elite to disseminate radical philosophies and effect geopolitical shifts while remaining safely insulated from state and religious censorship.1

The primary evidence for this “Impossible Genius” strategy lies in the staggering paradoxes surrounding the era’s most famous names. In literature, history presents the “Stratford Man,” an uneducated grain dealer from a family of illiterates, yet attributes to him the First Folio — a work requiring an unprecedented vocabulary of 29,000 words and intimate knowledge of international law and courtly life. A mirror image appears in the colonial record: Captain John Smith. Nominally a farm hand with limited schooling, Smith is credited with The Generall Historie, a text of such scholarly depth and prose quality that it rivals the Authorized King James Bible.

Were these men placeholders for Francis Bacon’s “New Atlantis” project? By examining the incongruencies in their biographies and the visual cues in their publications, we can see the outlines of a secret architecture designed to build a dual empire: one of language and one of soil.

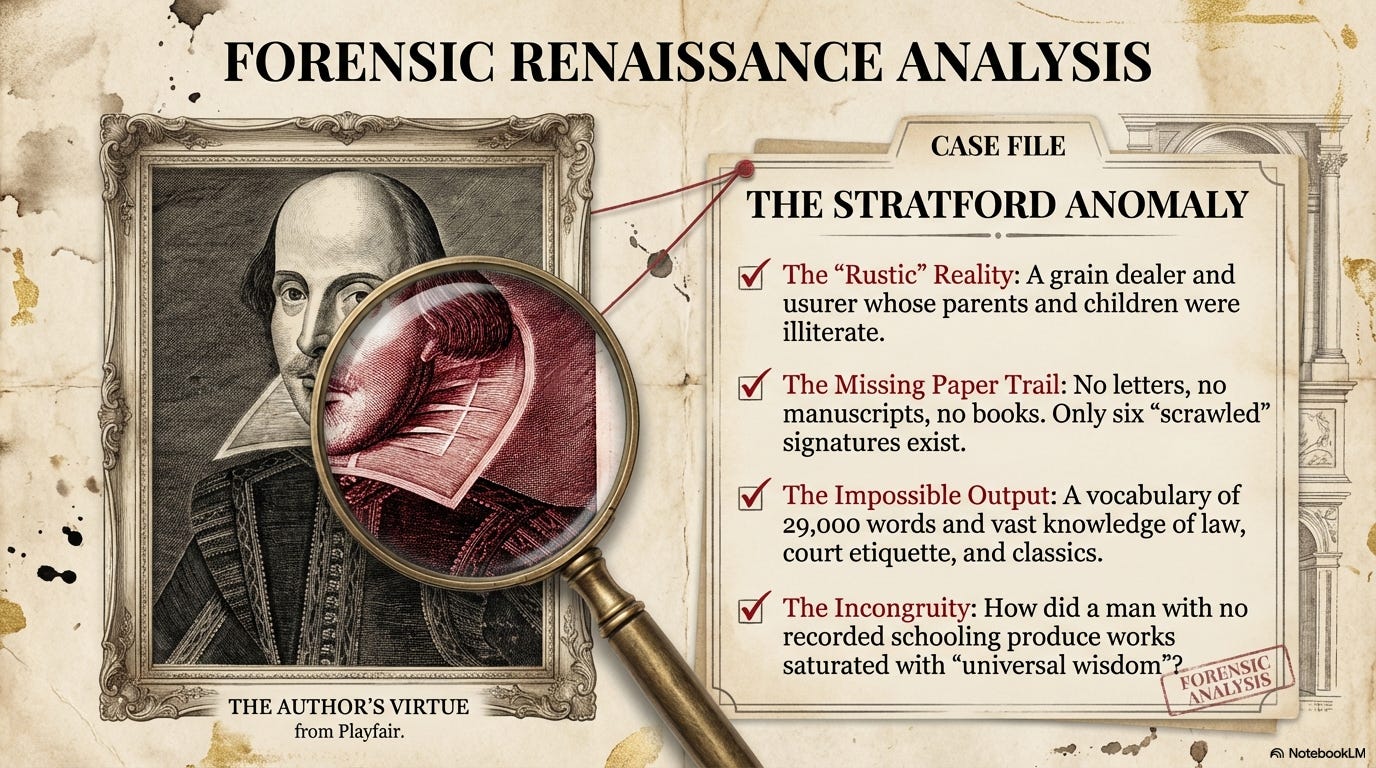

The Stratford Anomaly: Case File — William Shakespeare

Exhibit — The Rustic Playwright

The “Rustic” Reality vs. The Impossible Output

The man from Stratford-upon-Avon was an uneducated dealer in barley, wool, and real estate — a usurer whose parents and children were illiterate. He owned no books and left no letters, no manuscripts, and no correspondence. His six surviving signatures are illegible scrawls, suggesting he could barely hold a pen.2

Yet this same man is credited with producing the First Folio — a body of work that displays a vocabulary of 29,000 words, extensive knowledge of Greek and Latin literature, intimate familiarity with international law, court etiquette, military strategy, botany, medicine, and the inner workings of aristocratic life. As Mark Twain asked in his final book, how did a man with no recorded schooling produce works saturated with “universal wisdom”?3

The farcical idea that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon somehow managed to write dozens of plays of such enormous depth and complexity is, as researcher Robert Frederick writes, “an affront to the dignity of anyone who regards the truth as important.” Mainstream scholar Diana Price’s Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography has thoroughly documented the evidentiary vacuum surrounding the Stratford man’s connection to the plays — a case that even the University of London now offers courses on.4

At the Stratford man’s death, no one took any notice. There is no record of any ceremony. No obituary. No acknowledgment from the literary world that the greatest writer in the English language had just passed away.

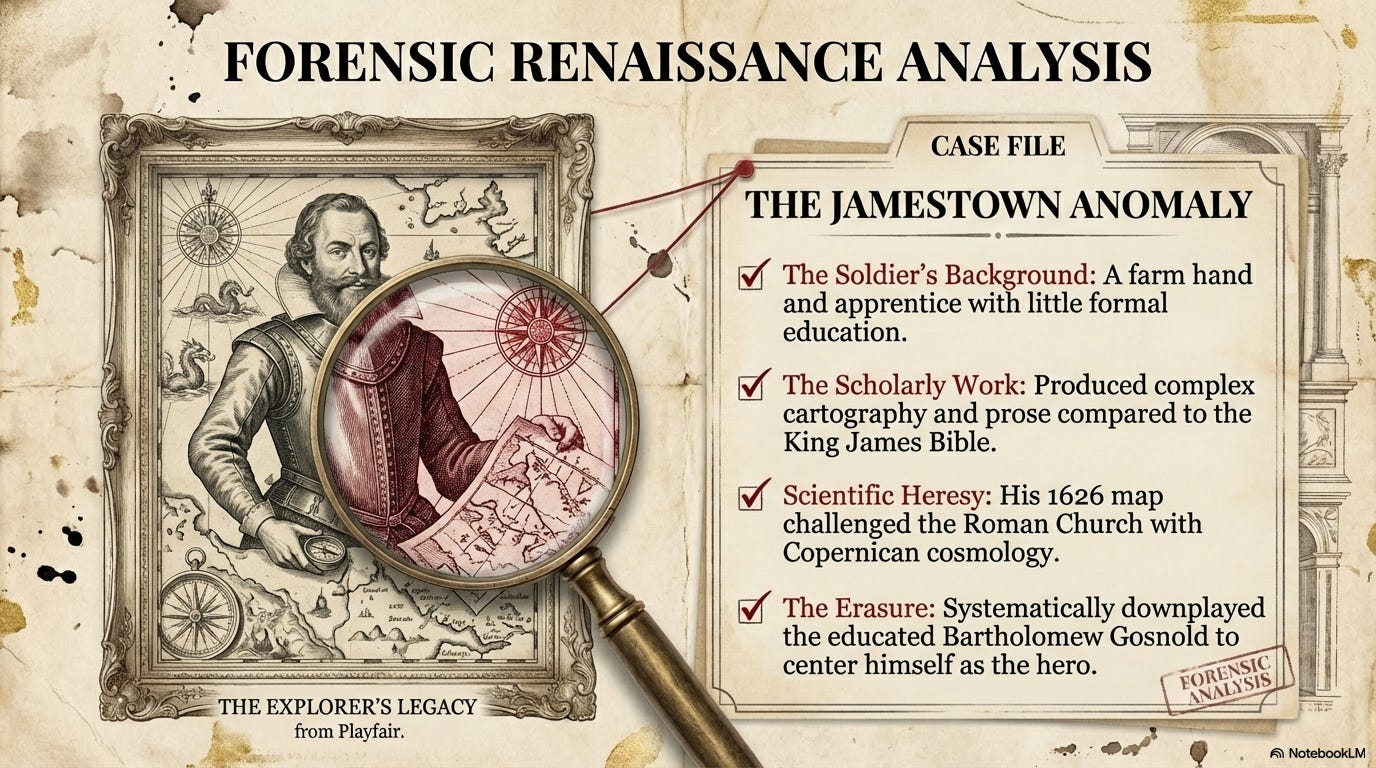

The Jamestown Anomaly: Case File — Captain John Smith

Exhibit — The Uneducated Captain

The Soldier’s Background vs. The Scholarly Work

John Smith was a Norfolk farmer’s boy who had been made a captain for valor while fighting as a mercenary in Hungary. He was a rough soldier-adventurer with little formal education — a farm hand and apprentice who had never attended university.5

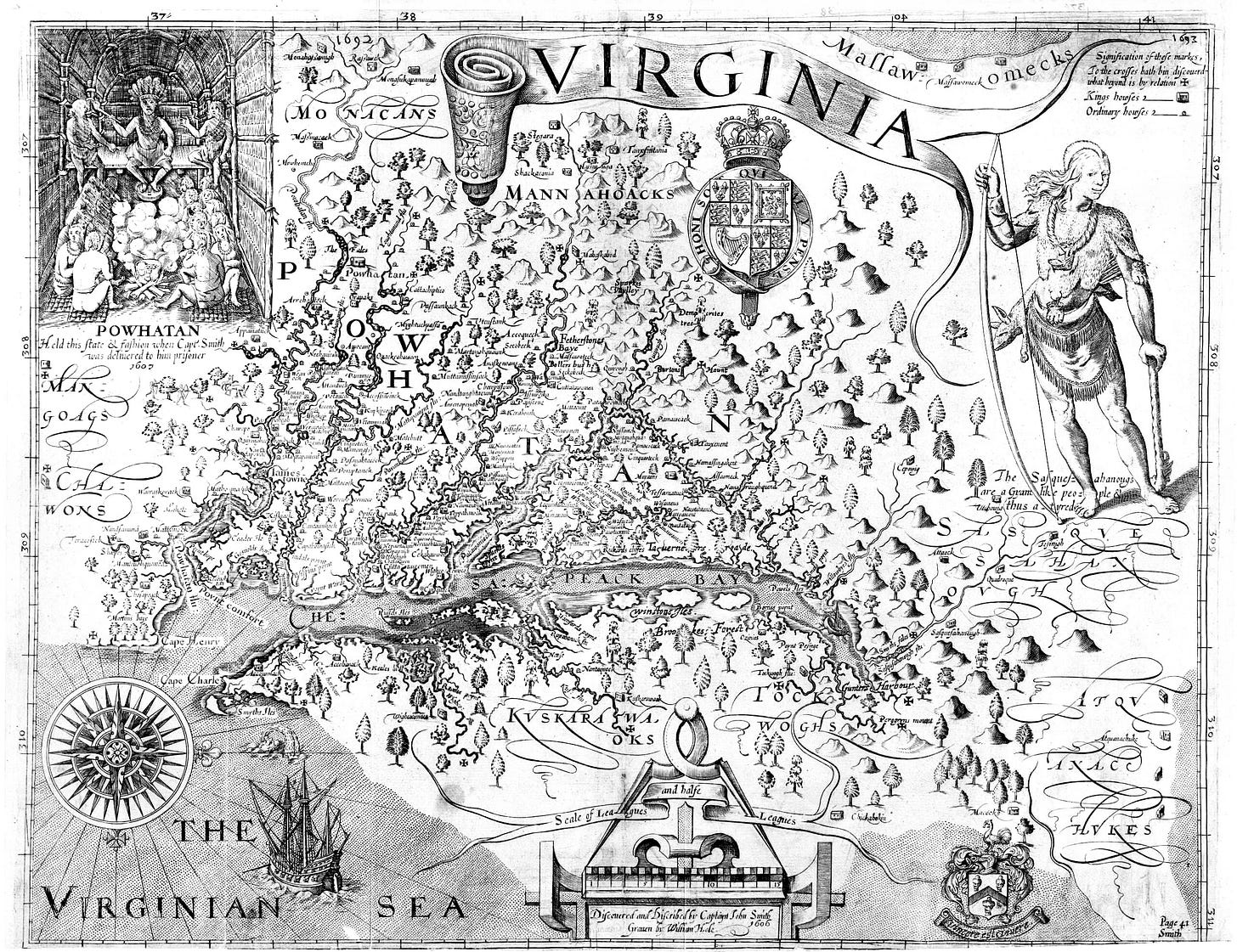

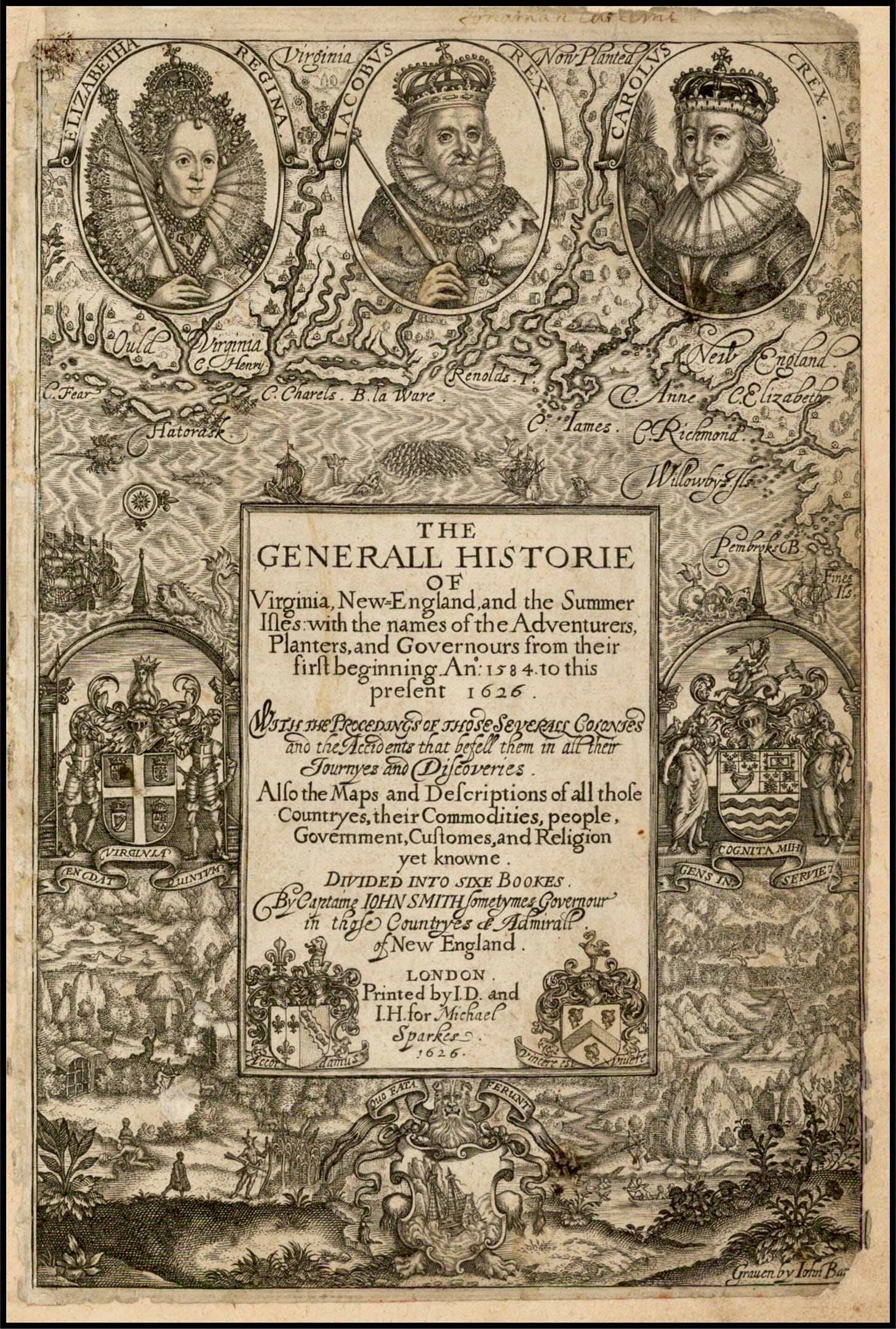

Yet Smith produced The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (1624) and A True Relation — works of complex cartography and prose so excellent they have been compared to the King James Bible.

His 1626 map contained Copernican cosmology that challenged the Roman Catholic Church, requiring the education of a university scholar, not a farmhand. Most critically, Smith systematically downplayed the role of Bartholomew Gosnold — the Cambridge-educated, legally trained “prime mover” of the Jamestown settlement — to center himself as the founding hero.6

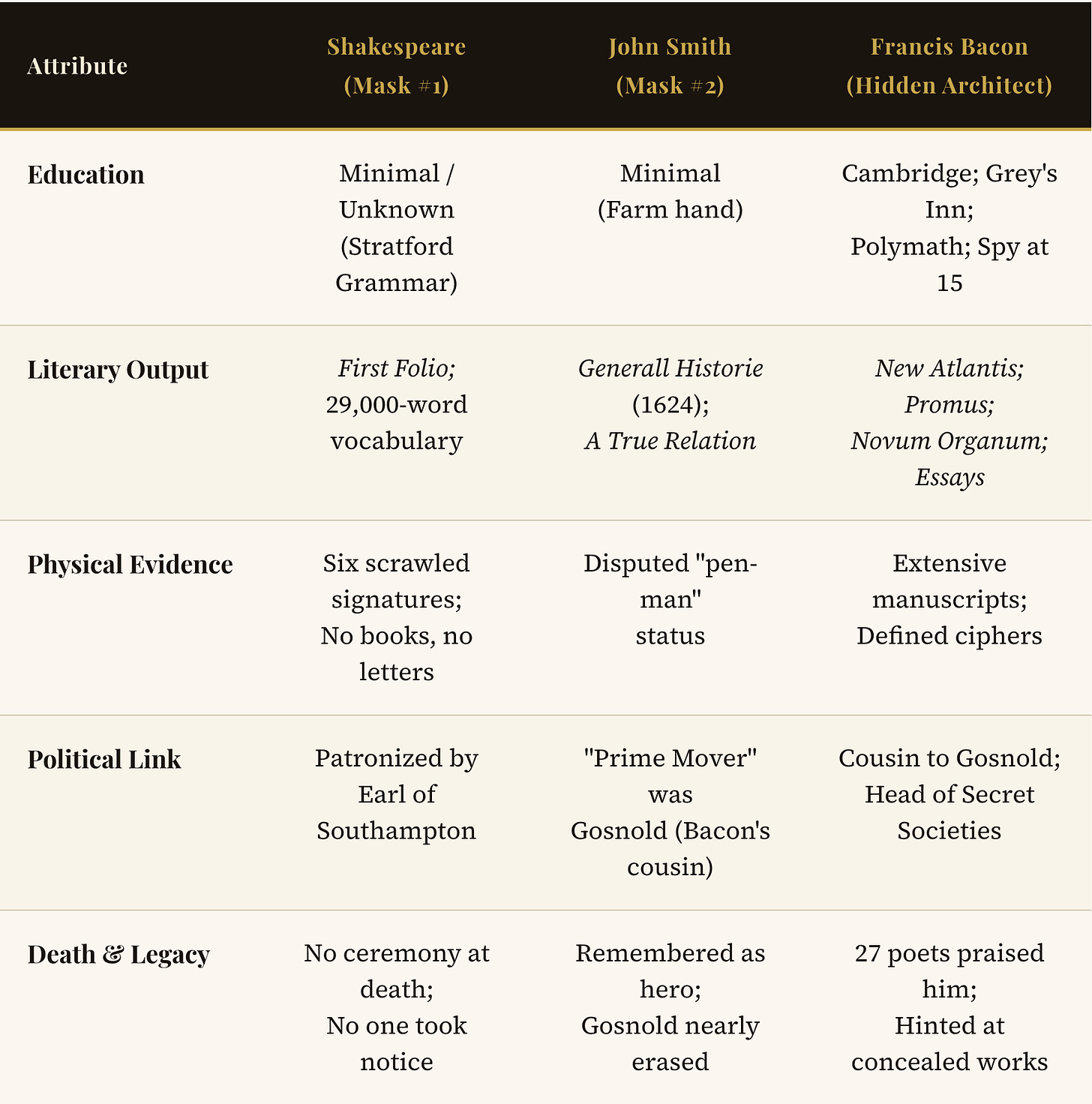

Comparative Analysis

The Scholar vs. the Surrogates

Part Two

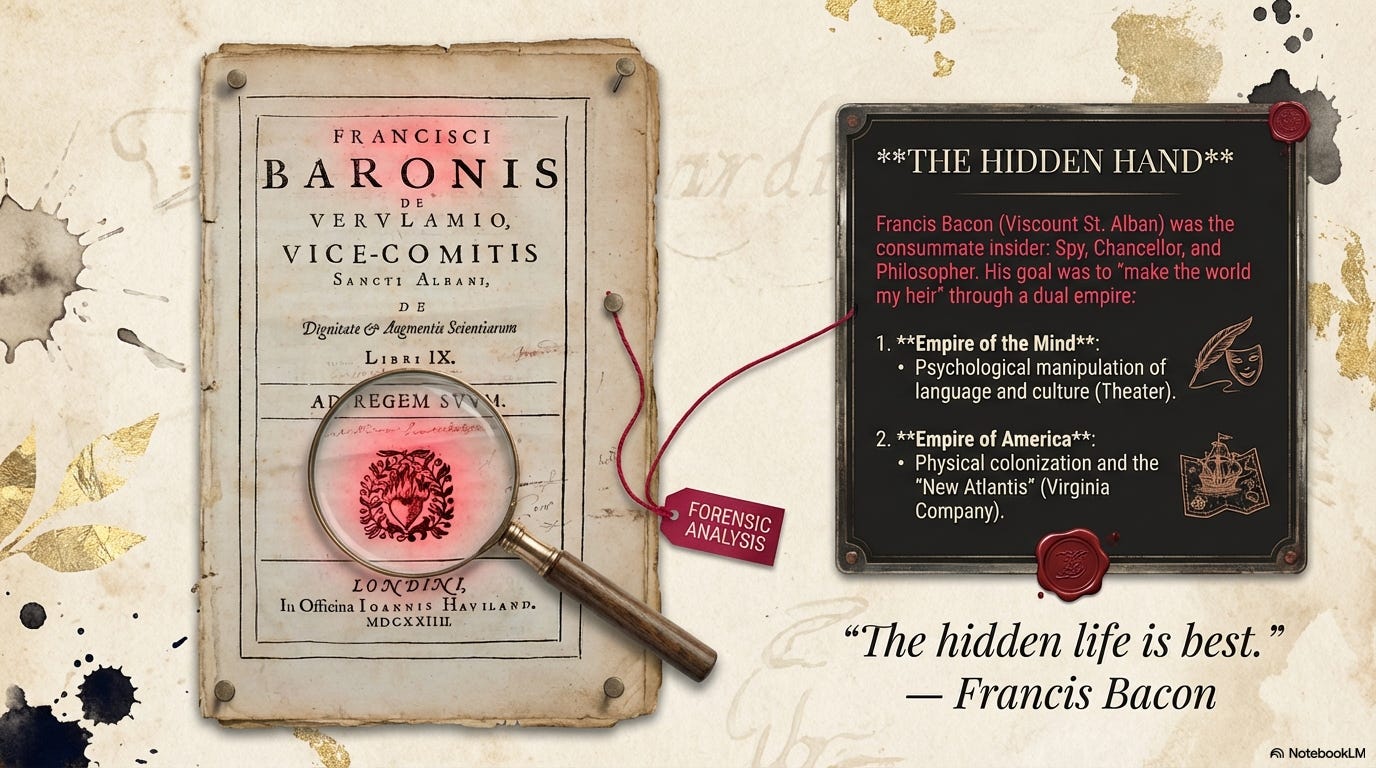

The Hidden Hand: Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon (1561–1626), Viscount St. Alban, was the consummate insider: spy, Chancellor, and philosopher. His stated goal was to “make the world my heir” through a dual strategy of intellectual and territorial empire. By the age of 15, he had mastered Greek, Latin, French, Hebrew, Spanish, and Italian, had read the entire classical canon in the original languages, and had already begun his career in espionage under spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham.7

“The hidden life is best.” ~ Francis Bacon

Bacon’s life presents a striking paradox. During the 25-year period in which the Shakespeare plays were written and first performed (c. 1582–1605), Bacon himself accomplished remarkably little in public. He was a lawyer who didn’t practice, a member of Parliament who rarely attended, and a man perpetually in debt yet always surrounded by servants. It was only after Queen Elizabeth died and King James took the throne that Bacon’s official career exploded — rising to Attorney General, Lord Chancellor, and Baron Verulam. It was only after his forced retirement in 1621 (on fabricated bribery charges, many scholars argue) that the First Folio was published in 1623, containing 18 plays that had never before appeared in print.8

At his death, 27 poets published tributes praising him as a genius across every field of human endeavor — many of them hinting that he was a “concealed poet” and the center of a great mystery meant to be unraveled by posterity.9

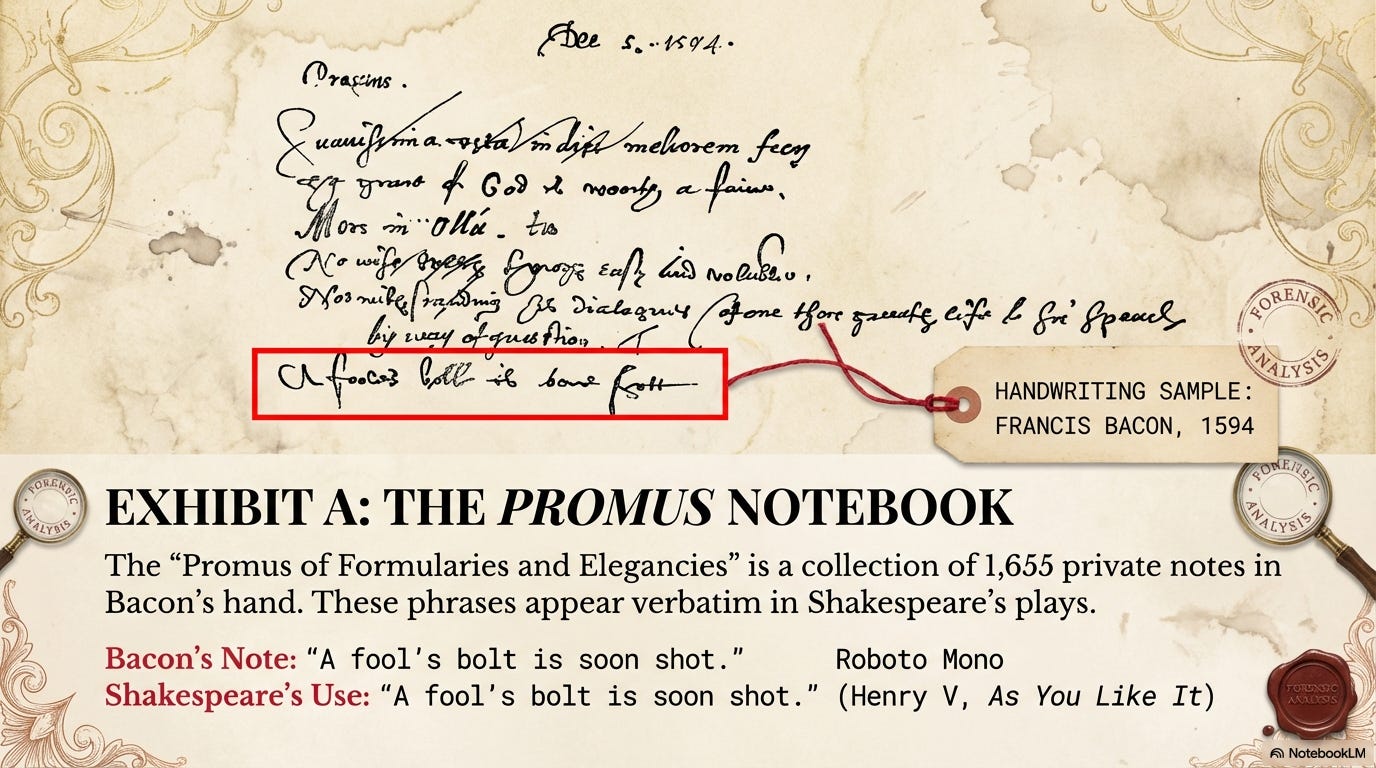

Exhibit A: The Promus Notebook — The Smoking Gun

Shakespeare Evidence

The Promus of Formularies and Elegancies

The Promus is a private collection of 1,655 phrases in Francis Bacon’s own handwriting, compiled c. 1594 and now held in the British Museum (MS Harley 7017). These exact proverbs and unique turns of phrase appear verbatim throughout the Shakespeare plays — sometimes word-for-word, sometimes adapted.10

Key Example:

Bacon’s Note: “A fool’s bolt is soon shot.”

Shakespeare’s Use: “A fool’s bolt is soon shot.”

— Henry V, Act III & As You Like It, Act V

Not a single page of the original manuscript exists connecting the Stratford man to any play. One page of the Promus contains infinitely more evidence for Bacon’s authorship than exists for William Shakespeare of Stratford.

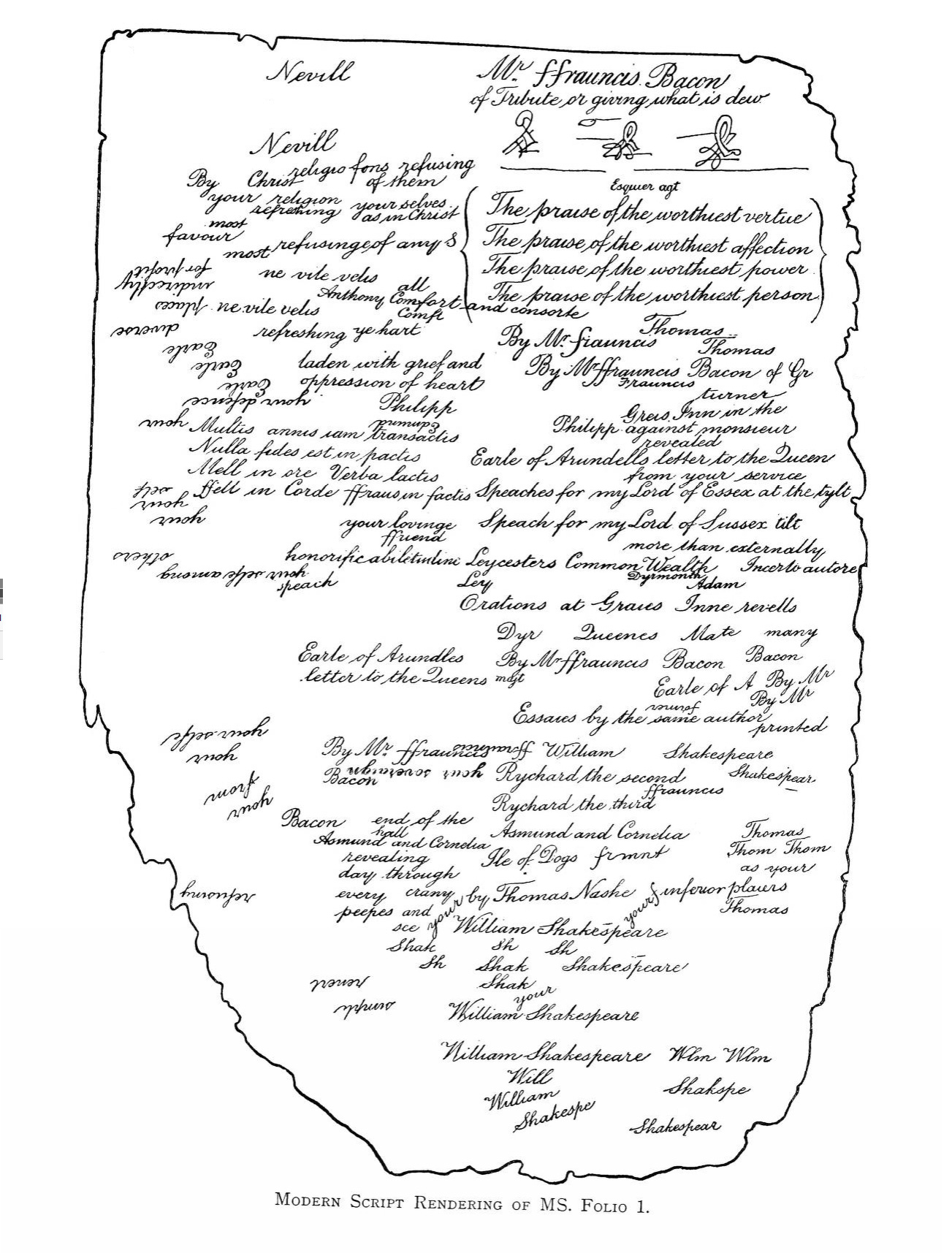

Exhibit B: The Northumberland Manuscript — The Physical Link

Shakespeare Evidence

The Northumberland Manuscript (c. 1590s)

Found at Alnwick Castle in 1867, among a folder of Francis Bacon’s writings, this cover sheet is the earliest known manuscript mention of Shakespeare. The names “Francis Bacon” and “William Shakespeare” are scribbled together repeatedly across the page — not as strangers, but as figures linked in the same workspace.11

The folder contained copies of Bacon’s speeches alongside Shakespeare’s Richard II and Richard III. This is a physical link — Bacon’s handwritten papers interleaved with Shakespeare’s plays — that no other authorship candidate can claim.

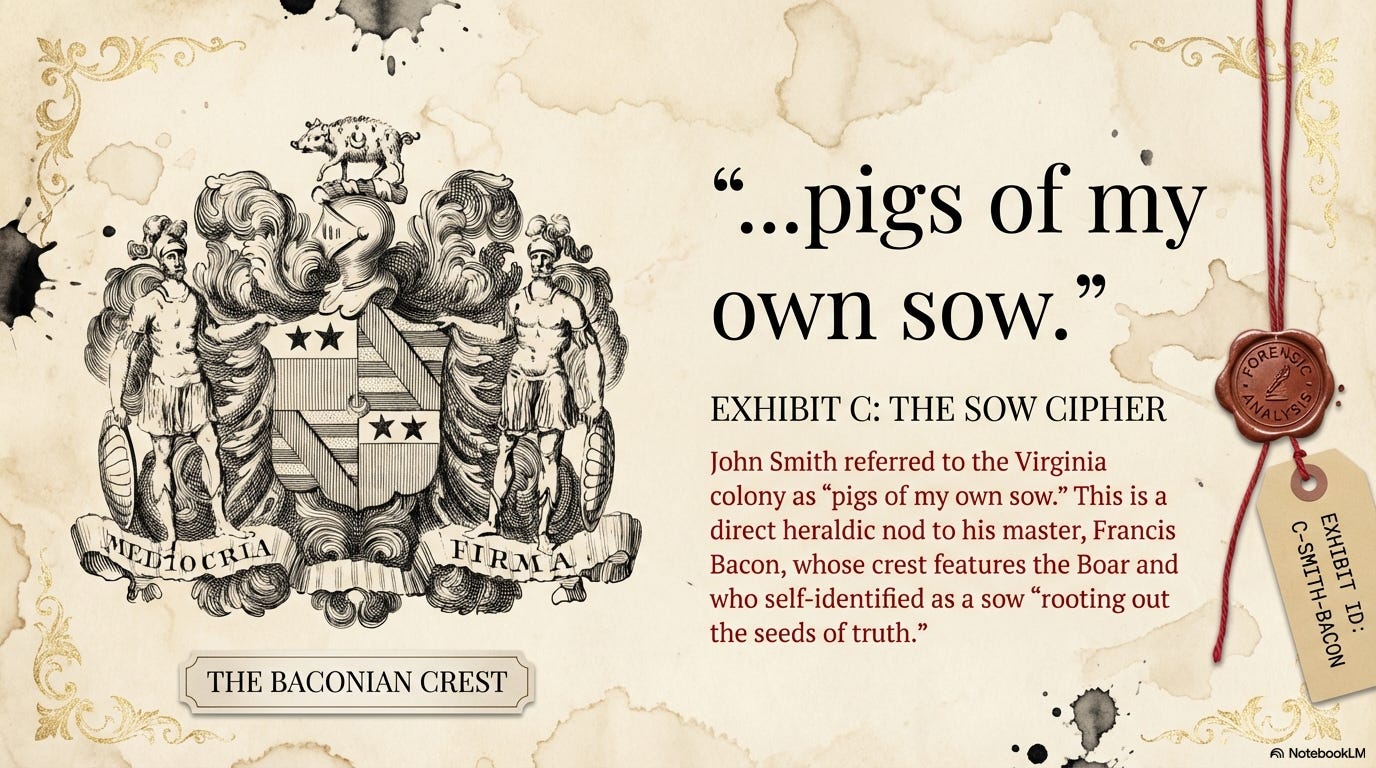

Exhibit C: The Bacon–Smith Connection — The Colonial Link

The Lost Letter

Smith Writes to Bacon

A letter from John Smith to Lord Bacon survives, enclosing a description of New England and discussing profits for the plantation. Does this directly link the colonial frontman to the intellectual architect — did Smith report to Bacon?

The “Sow” Cipher

Heraldic Acknowledgment

Smith referred to the Virginia colony as “pigs of my own sow” — a direct heraldic nod to Bacon’s family crest, which features a boar. Bacon self-identified as a sow “rooting out the seeds of truth.” Is this a coded acknowledgment of the master behind the mask?

The Gosnold Triple Link

Critical Connection

Bacon → Gosnold → Southampton → Shakespeare

Bartholomew Gosnold — Cambridge graduate, lawyer, and the “prime mover” of the Jamestown settlement — was Francis Bacon’s cousin (twice over).12 His uncle, Robert Gosnold III, served as the Earl of Essex’s secretary. His 1602 voyage was funded by the Earl of Southampton — the very same man who served as William Shakespeare’s patron.13

Gosnold organized the Jamestown voyage, interviewed and recruited 108 settlers from villages around Otley, Suffolk, and his wife’s cousin, Sir Thomas Smythe, funded and chartered the ships through the Virginia Company. Yet John Smith, whom Gosnold recruited as a subordinate, later credited himself as the central figure. As Nicholas Hagger writes: “John Smith, who later awarded himself much of the credit, was very much an underling who took no part during the first six months of the voyage.”14

This triple link — Bacon to Gosnold to Southampton to Shakespeare — strongly suggests an answer to the authorship question and the founding of America within a single circle of influence.

Part Three

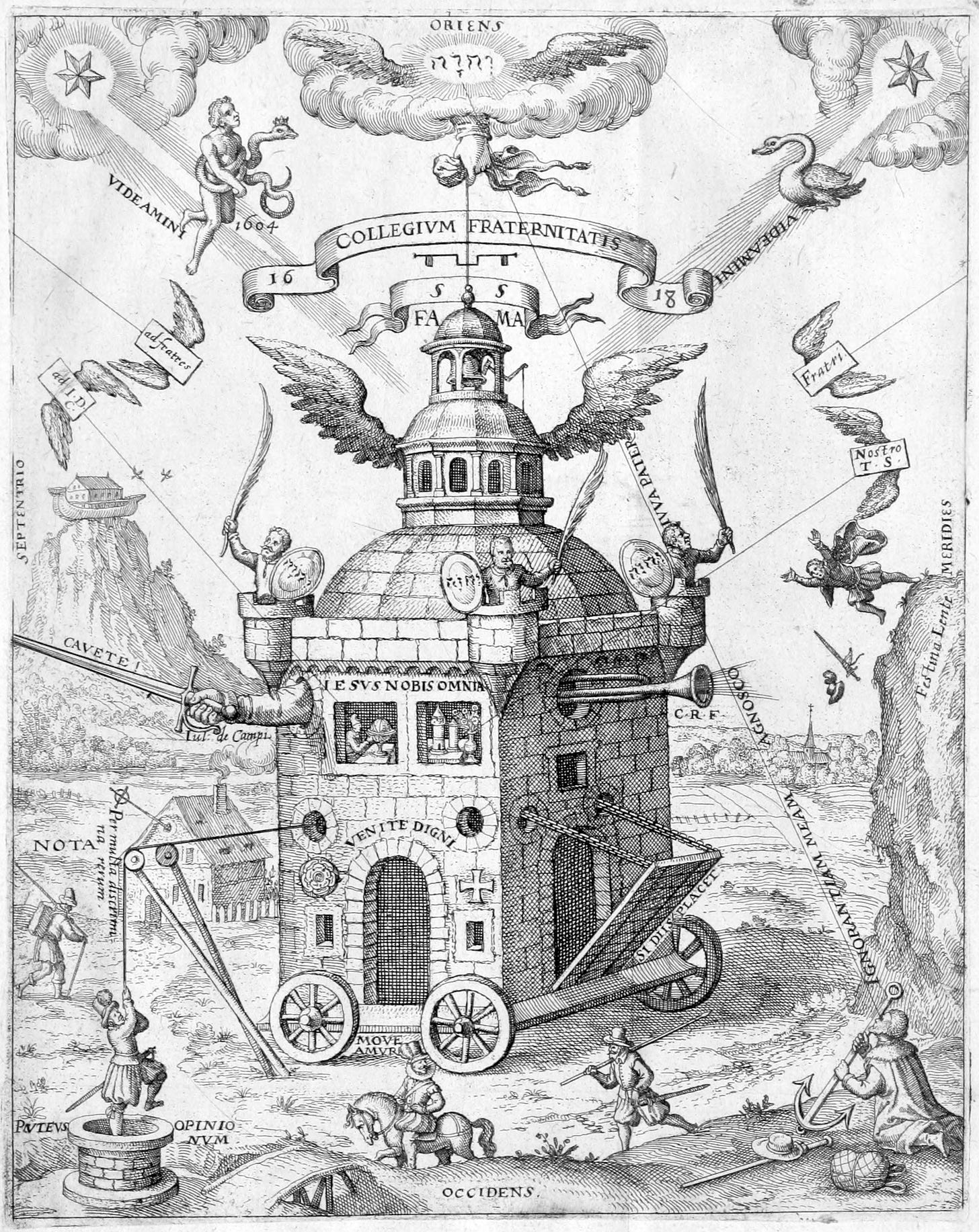

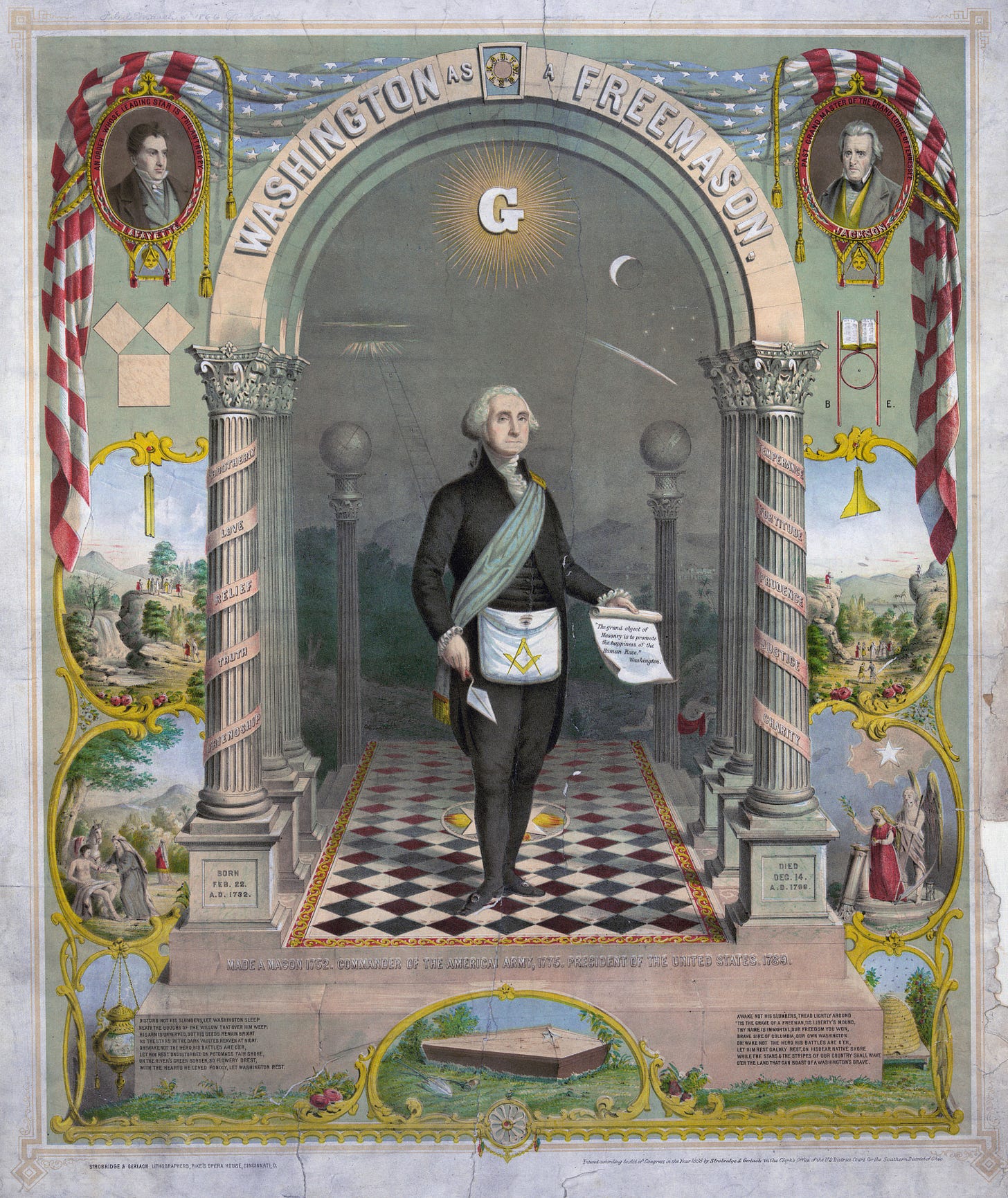

The Masonic Fingerprint

To ensure semiotic cohesion across the literary, religious, and colonial arms of the project, the “Invisible College” appears to utilize Masonic emblems as an encrypted branding system. These symbols function as a trademark, hidden in plain sight, for those initiated into the agenda of Elizabethan imperialism and the realization of the “New Atlantis.”

Identity in this mission was signaled through identical headpieces and tailpieces found across three primary texts of the era:

📖 First Folio (1623) • Shakespeare’s Plays • “AA” (Apollo/Athena) headpieces and ornamental light/dark scroll seals.

✝️ King James Bible (1611) • The Authorized Version • Identical ornamental headpieces and tailpiece patterns — shared printer’s marks.

🗺️ Generall Historie (1624) • John Smith’s Colonial Record • Same “AA” emblems and scroll ornaments — the colonial arm of the project. (Scroll up to see the map.)

These were deliberate visual signifiers that these texts — religious, literary, and colonial — originated from a single intellectual origin. This visual branding marked the boundaries of an “Empire of the Mind” and the “Empire of America,” signaling the rise of a scientific and secular world order under the guise of established institutions.15

Part Four

The Invisible College

In an age of lethal censorship — when three Separatist clerical leaders had been hanged in 1593, and public expressions of heresy or sedition could cost you your tongue — Bacon required a covert infrastructure to disseminate radical ideas and coordinate geopolitical expansion.16

Rosicrucianism and Freemasonry provided this infrastructure. Bacon’s circle — including Ben Jonson and the founders of the Royal Society — utilized a cell-like structure reminiscent of intelligence agencies. This “Masonic Infrastructure” coordinated the Virginia Company and the literary propaganda, insulating the aristocracy from direct blowback. It was a system of “Gnosis”: dividing those who know from those who simply watch the show.

“The action of the theatre… was carefully watched by the ancients…. and, indeed, many wise men and great philosophers have thought it to the mind as the bow to the fiddle: and certain it is that the minds of men in company are more open to affections and impressions than when alone.”

— Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning (1605)17

The secret network was responsible for the publication and promotion of a specific suite of works designed to reshape the world: the Authorized King James Bible (1611), the Shakespearean plays, and the works of John Smith. These were the three pillars of a philosophical “planting” of Baconian ideals — spreading Protestantism, English cultural dominance, and the empirical method across the globe.

Part Five

Synthesis: The Dual Empire

The 17th-century expansion followed a “dual-track” strategy that combined the psychological power of language with the physical reality of territorial colonization.

Empire of the Mind

Through Shakespeare's plays, the English language was refined from what Robert Frederick calls “an underdeveloped, guttural stepchild of German” into the richest, most flexible language in the world — a prerequisite for global empire.18 The History plays rebranded the Tudor regime as divine providence; The Tempest‘s Prospero — the magician who controls an island through books and spirits — served as Bacon’s self-portrait of the philosopher-king controlling the colonial narrative. Theater was the mass media of the age, and Shakespeare was its instrument.

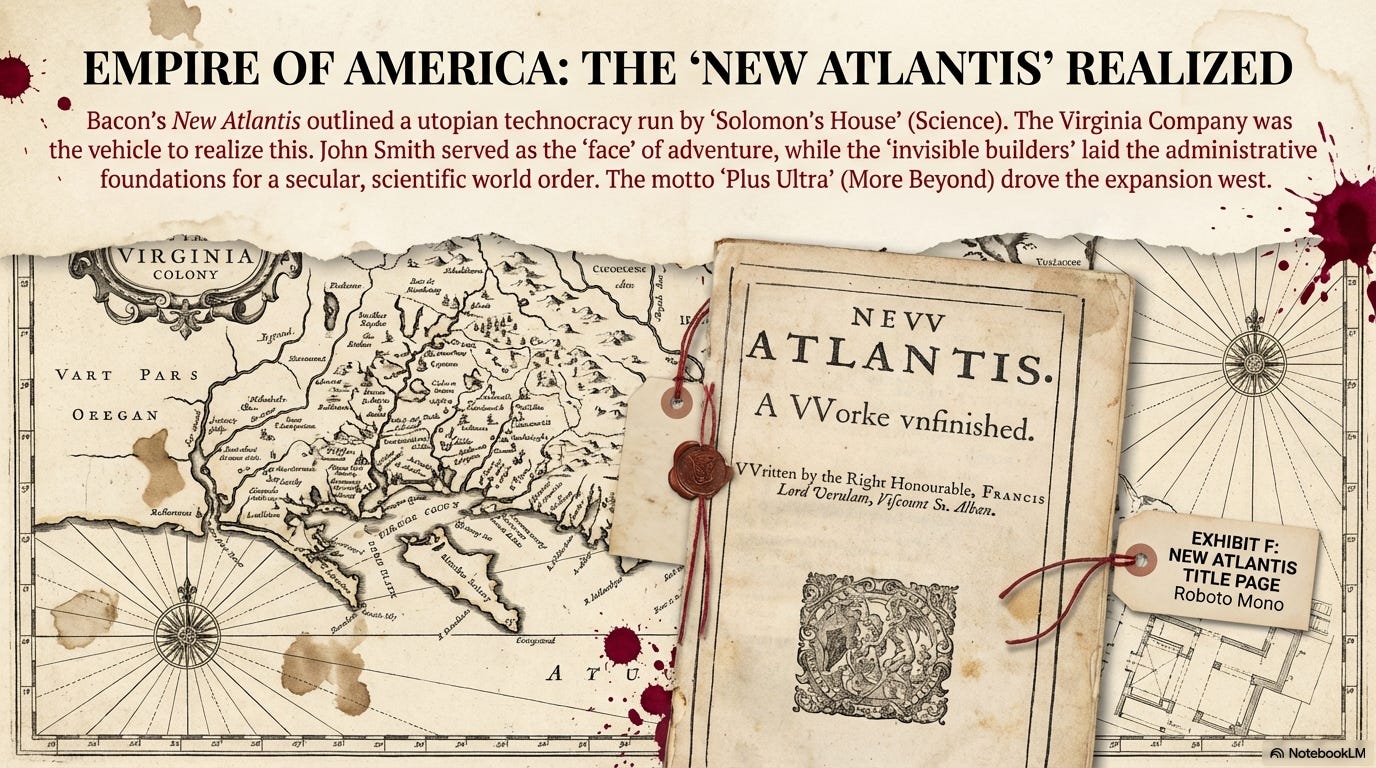

Empire of America

The Virginia colony represented the physical manifestation of the “georgic vision” outlined in Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627) — a utopian technocracy governed by “Solomon’s House” (science). This was not a pastoral or romanticized wilderness but a practical “georgic” project (after Virgil’s Georgics) of managing the estate of the world. Bacon sat on the board of the Virginia Company as lawyer and propagandist; his cousin Gosnold organized the Jamestown voyage; Gosnold’s wife’s cousin Sir Thomas Smythe funded and chartered the ships.19

John Smith served as the public “face” of adventure, while the “invisible builders” laid the administrative foundations for a secular, scientific world order. The motto Plus Ultra (“More Beyond”) drove westward expansion.

The Symbolic Structure

The decision to establish 13 colonies, proponents argue, was a deliberate nod to the secret architects’ lineage: 13 October 1307 was the date of the Templar persecution, and 13 represents the degrees of Templar initiation. By the time this “philosophical Atlantis” was fully rooted, Francis Bacon — the Secret Architect — had successfully shielded his grand design behind the masks of Shakespeare and Smith, laying the foundation for a secular, scientific world order that would eventually redefine the Western world.20

“Not only were many of the founders of the United States Government Masons, but they received aid from a secret and august body existing in Europe, which helped them to establish this country for a peculiar and particular purpose known only to the initiated few.”

— Professor Charles Eliot Norton of Harvard, c. 187621

Part Six

The Epistemological War

If even half of the above is true, then the founding mythology of both English literature and the American republic hinges on a deliberate act of concealment — an epistemological deception engineered at the highest levels of Elizabethan power and continually maintained, through institutional inertia and professional self-interest, for over four hundred years.

Consider the implications. The Promus notebook is on display at the British Museum for anyone to examine. The Northumberland Manuscript has been photographed, transcribed, and published online for your review. The familial connections between Bacon, Gosnold, Southampton, and the Virginia Company are matters of genealogical record, not speculation. The identical headpieces in the First Folio, the King James Bible, and the Generall Historie are visible to anyone who clicks the provided links.

These are hidden in plain sight, the signature method of EpiWar™️.

The question is not whether the evidence exists. It does. For practically any conspiracy you can come up with, evidence is lying all over the place. The question is why the evidence has been systematically ignored by the institutions responsible for investigating and disseminating it. Universities, journalism outlets, publishers, governments, and media all act as if it does not exist, or as if those who investigate are crazy.

The answer, once you see it, is uncomfortable in its simplicity: because the myth serves the same function now that it served then. Shakespeare, the self-made genius, validates a particular mythological story about English cultural supremacy — that greatness magically “emerges” from a chthonian miasma, or springs spontaneously from the soil of free nations, that no hidden hand guides the development of language, culture, or empire. John Smith, the fearless adventurer, supports a parallel myth — that America was founded by rugged individualists, not by a network of aristocratic secret societies implementing a philosophical blueprint. Both myths obscure the same truth: that the most consequential transformations in Western civilization were engineered, coordinated, and concealed by a small circle of initiated elites operating through layers of plausible deniability.

This is Epistemological Warfare — not a war fought with bullets and bombs, but a war fought over what you are allowed to know. The battlefield is not a geographic territory but the territory of your mind. The weapons are not firearms but narratives. And the casualties are not bodies but truths — truths buried so deep beneath layers of institutional consensus that even questioning them marks you as unserious.

The Bow Remains The Same

Bacon understood this. He wrote in the Advancement of Learning that the theater was to the mind what “the bow is to the fiddle” — the instrument by which the vibrations of an audience’s emotions could be tuned to a desired frequency. Four centuries later, the fiddle has changed shape — from the stage to the printing press to the television to the algorithm — but the bow remains the same. The principle of mass psychological manipulation through narrative control is the operating system of modern civilization.

The New Atlantis was a project plan, and we live in the world it envisioned.

If that claim strikes you as extraordinary, then ask yourself a simpler question: Why does every child in the English-speaking world learn the name William Shakespeare, but almost none learn the name Bartholomew Gosnold? Why is the man who actually organized the Jamestown voyage — a Cambridge-educated lawyer and cousin of the Lord Chancellor — virtually unknown, while the mercenary he recruited as a subordinate is celebrated as the founder of America?

The answer is that someone decided it should be that way. And that someone had the power, the infrastructure, and the motive to make it stick.

Stop swallowing the lies of so-called experts. Fact-check the assumptions presented here. Don’t take Peter Duke’s word for anything. Look at the Promus and the Northumberland Manuscript. Trace the Gosnold–Bacon–Southampton connections. Compare the headpieces. Follow the money through the Virginia Company, and then ask yourself whether the official story — that an illiterate grain dealer and a Norfolk farm hand independently produced two of the most consequential bodies of work in the English language, through sheer native genius and nothing more — is really the most plausible explanation for what you find.

“I have taken all knowledge to be my province.”

— Francis Bacon, Letter to Lord Burghley, 1592

He did.

And he hid it in the very place no one would think to look: everywhere.

Thanks to the generosity of my readers, all my articles are available for free access. Independent journalism, however, requires time and investment. If you found value in this article or any others, please consider sharing or even becoming a paid subscriber, who benefits by joining the conversation in the comments. I want you to know that your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. Please buy me a coffee or as many as you wish.

The Duke Report - Where to Start

My articles on SubStack are all free to read/listen to. If you load the Substack app on your phone, Substack will read the articles to you. (Convenient if you are driving).

Foundational Articles

Podcast (Audio & Video Content)

Palmerston’s Zoo Episode 01 - Solving the Paradox of Current World History (9 Episodes)

Oligarchic Control from the Renaissance to the Information Age

SoundCloud Book Podcasts

I’ve taken almost 200 foundational books for understanding how the world really works and posted them as audio podcasts on SoundCloud. If you load the app on your phone, you can listen to the AI robots discuss the books on your journeys across America.

Duke Report Books

Over 600 foundational books by journalists and academics that never made the New York Times Bestseller list, but somehow tell a history we never learned in school. LINK

Notes

The concept of “masks” as strategic surrogates is developed across multiple sources, synthesized primarily in Robert Frederick's “THE OVERWHELMING PROOF: Francis Bacon Wrote Shakespeare,” The Hidden Life Is Best (Substack), June 6, 2025.

Sir Edwin Durning-Lawrence, Bacon is Shake-speare (New York: The John McBride Co., 1910).

Price, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography; Frederick, “THE OVERWHELMING PROOF.”

Nicholas Hagger, The Secret Founding of America: The Real Story of Freemasons, Puritans, & the Battle for the New World (London: Watkins Publishing, 2007), Introduction.

John Smith, The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles (London: Michael Sparkes, 1624). For Gosnold as “prime mover,” see Hagger, Secret Founding, Ch. 2, where Smith himself is quoted writing that “Captain Bartholomew Gosnoll” was “one of the first movers of this plantation.”

Robert Frederick, “The Life and Times of Sir Francis Bacon,” The Hidden Life Is Best (podcast), 2025. https://thehiddenlifeisbest.com. See also Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning (London: Henrie Tomes, 1605).

Frederick, “THE OVERWHELMING PROOF.” The Shakespeare First Folio was published in 1623, seven years after the Stratford man’s death, containing 18 previously unpublished plays with extensive changes from earlier quartos.

Dr. William Rawley, ed., Manes Verulamiani (London, 1626), a collection of 32 elegies by 27 poets honoring Bacon’s death. Many contain veiled references to concealed literary production.

Francis Bacon, The Promus of Formularies and Elegancies, compiled c. 1594, British Museum, MS Harley 7017. The parallel between the Promus entries and the Shakespeare plays was first extensively documented by Mrs. Henry Pott, The Promus of Formularies and Elegancies by Francis Bacon (London: Longmans, Green, 1883).

The identical headpieces and tailpieces across the First Folio (1623), King James Bible (1611), and Smith’s Generall Historie (1624) are documented in Peter Dawkins, The Shakespeare Enigma (London: Polair Publishing, 2004).

Hagger, Secret Founding, Ch. 2. Bacon was MP for Ipswich (near Otley Hall, the Gosnold seat) from 1597, and “perhaps drew on Gosnold’s experiences in his New Atlantis.” Francis Bacon, New Atlantis, published posthumously in Sylva Sylvarum, or A Naturall Historie (London: William Lee, 1627).

This research is excellent! And once again, examing the Epistemological roots the myth of the America republic leads to very similar conclusions, that I have arrived at just by reading the text of the 2nd charter of the Virginia company (1609), (written by Francis Bacon who was the attorney for the Virgina Company at the time). Once you see what Bacon/London companies had in mind, and read American history through that prism, it is clear that reality reflects the Bacon/London vision, rather than the myth of the American Founding. American Freemasons (and other secret societies), masterminded the revolutionary war and established the territorial governments of all 37 states admitted after 1789. And in all cases, as they chartered cities and set up trading routes, they were looking out for the interests of a commercial/financial elite. According to Bacon's vision, the descendents of the Virginia company have always been the "owners" of America, and we are tenents on their properties.

So much of the narrative does not make sense. Example the 1609 map indicates they were aware of the general shape of North America and even named California and other states and yet we are told that in 1793, Sir Alexander Mackenzie, a Scottish-Canadian explorer and fur trader, was the first European to cross North America north of Mexico. What I find interesting is the Urbano Monte 1587 world map - with some of the same names. IMHO, most of our history has been fabricated.