In The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol, Dr. Terry Corey Brennan examines the fasces as a symbol of authority and its profound implications throughout history. Dr. Brennan served as the Andrew W. Mellon Professor at the American Academy in Rome from 2009-2012. He received two undergraduate degrees, from Penn (BA) and Oxford (BA and MA). Since receiving a Ph.D. in Classics from Harvard in 1990, he has taught at Bryn Mawr College (1990-2000) and Rutgers University (2000 to present). (Dr. Brennan also played guitar in the late ‘80s and early’ 90s for the Boston rock group The Lemonheads.)

Among its many layers, the book explores the role of lictors and the fasces in Roman governance, particularly as a symbol of justice and coercion. Brennan highlights the significant contributions of Cicero, one of Rome’s most influential statesmen, who critiqued the misuse of power symbolized by the fasces, arguing for ethical governance and the rule of law.

The fasces is a symbol of authority that originated in Etruscan society and became a cornerstone of Roman political and military culture. Defined by a bundle of rods bound around an axe, the fasces represented imperium—the power to govern and enforce order. Its historical journey includes adoption in the Roman Republic, reinterpretation during the Renaissance, incorporation into revolutionary iconography, and its most controversial use under Benito Mussolini in Fascist Italy. This analysis explores the fasces’ symbolic evolution and how it has been used to reflect authority, unity, and governance.

Thanks to my readers' generosity, all my articles are free to access. Independent journalism, however, requires time and investment. If you found value in this article or any others, please consider sharing or even becoming a paid subscriber, who benefits by joining the conversation in the comments. I want you to know that your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. Please buy me a coffee or as many as you wish.

GPT Summary

🌄 Origins in Etruscan Culture

The fasces originated with the Etruscan League of Twelve Cities, where it symbolized the collective power of their magistrates. Each city contributed a lictor, who carried the fasces to represent the unity of the league during military campaigns. Archaeological discoveries, such as the “Tomb of the Lictor” in Vetulonia, highlight the fasces’ ceremonial and functional significance. The rods in the fasces represented corporal punishment, while the axe symbolized the magistrate’s authority to impose capital punishment. The Etruscan influence on Roman culture ensured that the fasces became a symbol of power and governance in Rome as well.

👑 Monarchy of Rome

Under the Roman monarchy, the fasces symbolized the supreme imperium of the king. Tarquinius Priscus, an Etruscan king of Rome, introduced the fasces as a marker of the king’s control over life, death, and the enforcement of justice. Twelve lictors, each carrying a fasces, accompanied the king, underscoring his unchallengeable authority. The axe within the fasces emphasized the king’s ability to impose capital punishment without appeal. This period established the fasces as a visible symbol of centralized control and governance.

🏛️ Transition to the Republic

The abolition of the monarchy in 509 BCE transformed the fasces into a symbol of Republican ideals. The fasces now represented the imperium of the Roman consuls, who were annually elected and held joint authority. Consuls alternated possession of the fasces each month to reflect the principle of shared governance. Reforms by Publius Valerius Publicola ensured that the fasces symbolized respect for the citizenry. These changes included removing the axe within city limits to protect citizens’ rights and instructing lictors to lower the fasces in assemblies, signifying the supremacy of the people. Publicola’s adjustments reinforced the ideals of accountability and shared power in the fledgling Republic.

🔨 Lictors and Their Roles

Lictors, the officials tasked with carrying the fasces, played an integral role in enforcing the authority of magistrates. They were responsible for maintaining order, protecting officials, and executing punishments. The rods in the fasces symbolized the magistrate’s power to impose corporal punishment, while the axe signified the ultimate authority to carry out executions. Lictors’ presence in public spaces highlighted the real and symbolic power of Roman magistrates, ensuring compliance and reverence for the law.

🏰 The Fasces Under the Empire

During the Roman Empire, the fasces remained a potent symbol of imperium, although its use became more ceremonial. Emperors expanded their symbolic representation by increasing the number of lictors and fasces. The fasces served to reinforce the centralized power of the emperor while maintaining continuity with Republican traditions. The symbol also extended to municipal governance and certain priesthoods, emphasizing its adaptability in representing authority across various contexts.

🎨 Renaissance Revival of the Fasces

During the Renaissance, the fasces reemerged as a metaphor for unity and strength. Drawing inspiration from Aesop’s fable “The Bundle of Sticks,” the fasces became a visual and literary symbol of collective power. In cities like Florence, the fasces was prominently displayed in public art, often reflecting the Renaissance’s reverence for classical antiquity. The reinterpretation of the fasces during this period emphasized cooperation and unity over the coercive power it had symbolized in earlier times.

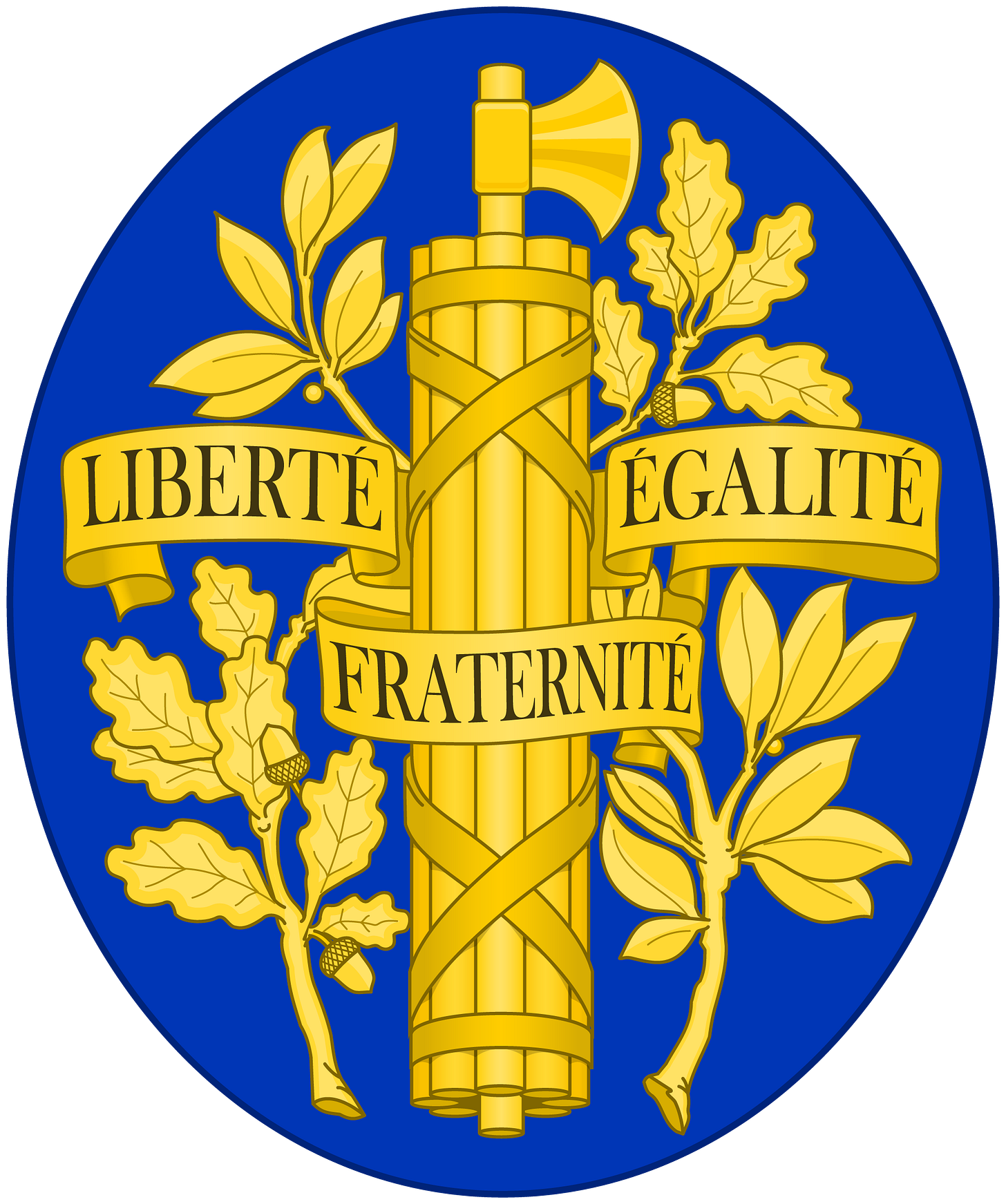

⚔️ Revolutionary France

The fasces played a central role in the imagery of the French Revolution, representing liberty, equality, and fraternity. Revolutionary leaders adopted the fasces as a symbol of collective power and the people’s sovereignty over the monarchy. The fasces appeared on coins, emblems, and public monuments as a symbol of the strength of unified citizens against tyranny. This adaptation marked a shift in the fasces’ meaning, associating it with democracy and popular governance rather than authoritarian rule.

🇺🇸 The Fasces in the United States

In the United States, the fasces symbolized unity and authority. It was prominently incorporated into federal symbolism, including the Mace of the House of Representatives and the architecture of the Lincoln Memorial. Unlike its later use in Fascist Italy, the American fasces emphasized democratic governance and the principle of collective strength. Its presence in the United States underscores its versatility as a symbol, unlinked to its Roman or Fascist connotations in this context.

⚡ Fascist Italy and Mussolini’s Reinterpretation

In the 20th century, Benito Mussolini used the fasces as the emblem of the Fascist Party, transforming it into a symbol of authoritarian unity and power. Declared the national emblem of Italy in 1926, the fasces appeared in propaganda, public architecture, and state ceremonies. Mussolini’s efforts to reconstruct an “authentic” Roman fasces emphasized its martial and coercive elements, while discarding its historical associations with shared governance. The fascist reinterpretation of the fasces left a lasting impact on its modern connotations.

🌍 Post-Fascist Legacy and Modern Interpretations

After the fall of Mussolini’s regime, efforts to disassociate the fasces from Fascism emerged, especially in Italy. In countries like the United States, where the fasces had broader symbolic meanings, it continued to symbolize legitimate authority and unity. However, its layered history — spanning its Roman origins, democratic adaptations, and fascist appropriations — has made it a contested symbol. Its modern usage requires careful contextualization to separate its authoritarian implications from its historical significance as a symbol of governance and unity.

🌟 Conclusion of Overview

The fasces encapsulates the evolution of authority from Etruscan practices to modern political ideologies. Its ability to serve vastly different purposes, from representing liberty and democracy to authoritarianism, highlights the enduring power of symbols to shape and reflect political and cultural values.

The Rods and Corporal Punishment

The rods symbolized the magistrate’s authority to maintain order through physical discipline. They were used to enforce laws among Roman citizens, slaves, and non-citizens, underscoring the practical aspects of imperium in daily life. Lictors, attendants tasked with carrying the fasces, would use the rods to clear pathways, control unruly crowds, and enforce minor sentences immediately upon a magistrate’s order.

For example, during the early Republic, consuls wielding the fasces were empowered to punish soldiers or citizens guilty of insubordination or public disturbances. The rods represent immediate and enforceable justice, ensuring compliance with Roman law. The symbolic bundling of the rods also highlighted the importance of collective strength and unity in supporting societal order.

The Axe and Capital Punishment

The axe within the fasces represented the ultimate authority of the magistrate to impose capital punishment. This authority was especially significant in military or frontier contexts, where Roman officials acted as both judges and enforcers of law. The presence of the axe in the fasces highlighted the magistrate’s capacity to execute individuals deemed a threat to Roman stability or security.

If you value this work, consider leaving a tip at Buy Me A Coffee.

Lucius Junius Brutus, one of the first consuls of the Republic, famously demonstrated this authority when he ordered the execution of his own sons for conspiring to restore the monarchy. The inclusion of the axe in the fasces during this event reinforced the magistrate’s commitment to justice and the prioritization of the Republic over personal ties.

Within the city of Rome, however, the axe was removed from the fasces to reflect the citizens’ right of appeal against a magistrate’s capital decision. This modification symbolized the limits of magisterial power within the city, where the sovereignty of the people and their protection under Roman law were paramount. Publicola’s reforms, which required the removal of the axe in urban contexts, ensured that the fasces remained a symbol of both power and respect for citizen rights.

Military and Provincial Uses of the Fasces

In military settings, the fasces retained the axe to underscore the unchallenged authority of commanders. Consuls and generals, carrying the fasces into battle, wielded the power of life and death over soldiers and subordinates. The rods symbolized discipline, while the axe served as a warning of the consequences of disobedience or treason.

In provincial governance, the fasces carried by governors represented their imperium over non-citizens. The authority to administer corporal and capital punishment without appeal emphasized the Roman state’s control over its territories and underscored the hierarchy between Roman officials and the governed populations.

Symbolic Adaptations and Philosophical Implications

The dual components of the fasces reflected broader Roman ideals about governance and authority. The rods emphasized the importance of collective strength and unity — qualities that were essential to Rome’s success as a city-state and later as an empire. The axe, in contrast, represented the decisive, often harsh nature of Roman justice.

This duality was expressed in the philosophical writings of figures like Cicero, who referenced the fasces in his discussions on justice and governance. Cicero argued that the fasces symbolized both the responsibilities and the limitations of power. His critiques of figures like Gaius Verres, who abused their authority as magistrates, illustrate the ethical weight carried by those who wielded the fasces.

Public Displays and Civic Ceremonies

In public ceremonies, the fasces was a constant reminder of the magistrate’s power and responsibilities. Lictors, dressed in traditional attire, marched in procession ahead of magistrates, carrying the fasces as symbols of their imperium. The number of fasces varied by office:

Consuls were accompanied by twelve lictors, reflecting their supreme authority.

Praetors, lower-ranking magistrates, were assigned six lictors.

Dictators, during emergencies, were granted twenty-four lictors, doubling the standard number to signify extraordinary powers.

These displays reinforced the hierarchical structure of Roman government and the respect demanded by officials holding imperium.

One notable ceremonial use of the fasces occurred during triumphal processions, where victorious generals were celebrated in public parades. Lictors carrying fasces led these processions, emphasizing the general’s temporary imperium, granted for military campaigns. During the Republic, such displays were strictly regulated to prevent individuals from overstepping their authority.

The Fasces in the Forum

In the Roman Forum, the fasces symbolized both authority and accountability. When magistrates presided over legal proceedings or assemblies, lictors bearing fasces stood as visible reminders of the magistrate’s power to enforce rulings. Public assemblies often witnessed the symbolic lowering of the fasces, signaling respect for the people’s sovereignty and adherence to the principle that the source of a magistrate’s authority ultimately rested with the citizenry.

For example, Publius Valerius Publicola’s reforms mandated this practice to affirm the Republic’s commitment to popular sovereignty. Such displays transformed the fasces from a purely coercive symbol to one that also embodied civic responsibility.

Military Campaigns and Discipline

The fasces played a vital role in maintaining discipline within the Roman military. In times of war, generals carrying the fasces had absolute authority over their troops. The rods signified the enforcement of military discipline through corporal punishment, while the axe represented the ultimate penalty of execution for insubordination or desertion.

One of the most famous military applications of the fasces occurred during the campaigns of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, a general and later dictator. Sulla’s command over his troops was reinforced by the visible presence of the fasces, which reminded soldiers of the unyielding authority of their commander.

In provincial settings, governors carried fasces to symbolize their authority over non-citizen populations. The inclusion of the axe in these contexts highlighted their power to impose capital punishment without appeal, a prerogative reserved for magistrates governing territories beyond the city of Rome.

Religious and Ritual Contexts

The fasces also held significance in religious ceremonies. Priestly officials, such as flamens (priests dedicated to specific gods), were occasionally accompanied by lictors carrying fasces, symbolizing their quasi-magisterial status. These ceremonial uses emphasized the divine sanction of authority in Roman society.

During public sacrifices and oaths of allegiance, the fasces served as a backdrop, reinforcing the sacred connection between Rome’s gods, laws, and leaders. This blending of political and religious authority ensured the fasces remained a central element of Roman identity and governance.

Historical Examples of Symbolism in Action

Lucius Junius Brutus and Republican Ideals

After the expulsion of the monarchy, Lucius Junius Brutus used the fasces to reinforce the transition to Republican governance. When his sons conspired to restore the monarchy, Brutus ordered their execution, demonstrating the impartiality of justice under the fasces. This act of sacrificing personal ties for the sake of the Republic solidified the fasces as a symbol of collective duty and the prioritization of public good over private interests.

Publicola’s Reforms

The removal of the axe from the fasces within Rome and the practice of lowering the fasces before the people were reforms implemented by Publius Valerius Publicola to ensure that the fasces reflected Republican values. These changes balanced the display of magisterial authority with respect for individual rights, fostering trust in the new Republic.

Julius Caesar and the Fasces

During his dictatorship, Julius Caesar expanded the use of the fasces as a display of his consolidated power. Caesar’s decision to carry the fasces in public, accompanied by twenty-four lictors (reserved for dictators), underscored his exceptional authority. However, this symbolic expansion also fueled tensions leading to his assassination, as it was seen as an encroachment on Republican principles.

Mussolini’s Revival of the Fasces

In Fascist Italy, Benito Mussolini reinterpreted the fasces as a symbol of authoritarian unity. Architectural projects in Rome, such as the EUR district, prominently featured fasces imagery, linking the regime to Rome’s imperial past. Mussolini’s appropriation stripped the fasces of its Republican and democratic associations, transforming it into a purely authoritarian emblem.

Lictors

Comprehensive Overview of Lictors

Lictors were essential figures in Roman public life, serving as attendants to magistrates and embodying the authority represented by the fasces. Their role was both symbolic and functional, blending ceremonial importance with practical enforcement duties. Below is a detailed account of their origins, duties, hierarchical associations, and significance in Roman culture.

Origins and Symbolic Importance

Lictors originated in Etruscan culture, where they accompanied rulers and carried fasces as a sign of the magistrate’s imperium. When Rome adopted the fasces, the lictors became visible agents of this power, symbolizing the magistrate’s ability to enforce laws and administer justice. Their presence was a constant reminder of the magistrate’s authority, both to protect and to punish.

Duties of Lictors

Lictors performed a wide range of duties that were vital to the execution of Roman governance:

Carrying the Fasces: Lictors carried the fasces, a bundle of rods often bound with an axe, which symbolized the magistrate’s imperium. The rods denoted corporal punishment, and the axe represented the authority to impose capital punishment.

Clearing Paths: Lictors ensured the magistrate’s passage through crowded streets by using their staff to clear pathways, asserting the importance of the magistrate’s presence.

Public Announcements: Lictors acted as heralds, declaring official edicts, calling assemblies, and summoning individuals to appear before the magistrate.

Ceremonial Attendance: Lictors accompanied magistrates in public processions, legal assemblies, and religious ceremonies. Their number and position in these events reflected the rank and importance of the magistrate.

Enforcement of Punishment: Lictors carried out corporal and capital punishment as directed by the magistrate. The rods were used for public beatings, while the axe signified the power to execute.

Hierarchical Associations

The number of lictors accompanying a magistrate directly corresponded to the rank and scope of the magistrate’s imperium:

Consuls: Each consul was assigned twelve lictors, reflecting their supreme imperium.

Praetors: Lower-ranking magistrates, such as praetors, were accompanied by six lictors.

Dictators: During emergencies, dictators were granted twenty-four lictors, emphasizing their extraordinary authority over all other officials.

Censors: Although primarily administrative, censors were occasionally accompanied by lictors during public ceremonies to signify their authority.

Flamens and Priests: Some high-ranking priests were provided lictors, reflecting the intersection of religious and political authority.

City and Military Contexts

The duties and presence of lictors varied depending on whether they operated within the city or in a military setting:

Within the City of Rome: Inside the city, the axe was removed from the fasces to signify the rights of Roman citizens, including their right to appeal a magistrate’s decisions. This adjustment demonstrated the limitations of magisterial power within the city and respect for Roman legal protections.

In Military and Provincial Contexts: Outside the city, lictors carried fasces with the axe intact, highlighting the magistrate’s unrestrained imperium. Generals and provincial governors relied on lictors to enforce discipline, maintain order, and carry out punishments without the need for appeal.

Ceremonial Role

Lictors were indispensable in public ceremonies, reinforcing the legitimacy and authority of Roman officials. During triumphal processions, lictors marched in front of victorious generals, their fasces emphasizing the general’s imperium. At state funerals, lictors reversed their fasces as a gesture of mourning, reflecting the loss of the magistrate’s authority upon their death.

Social Perception and Representation

Lictors were simultaneously respected and feared. Their role as enforcers of justice made them indispensable to the magistrate, but their association with corporal and capital punishment also evoked public apprehension. In literature, lictors were often depicted as stern figures who embodied the coercive power of the state.

Cicero referenced lictors in his speeches, portraying them as instruments of both justice and tyranny, depending on the character of the magistrate they served. His critiques of corrupt officials, like Gaius Verres, highlighted the potential for lictors to be misused as tools of oppression when serving unethical leaders.

Famous Examples

Lucius Junius Brutus’ Lictors

As one of the first consuls, Lucius Junius Brutus’ lictors carried fasces to signify his imperium during the early Republic. Brutus’ execution of his sons for conspiring to restore the monarchy was carried out under the authority of his lictors, solidifying their role in enforcing the magistrate’s power and the principles of the Republic.

Julius Caesar’s Expanded Lictors

During his dictatorship, Julius Caesar doubled the number of lictors accompanying him, reflecting his consolidation of power. This use of lictors as a display of exceptional authority contributed to tensions with those who opposed his perceived overreach of Republican norms.

Mussolini’s Reinterpretation

In Fascist Italy, Mussolini’s appropriation of the fasces included lictor-like figures in state processions and propaganda, symbolizing the regime’s continuity with Roman authority. While these figures were largely ceremonial, they borrowed heavily from the visual legacy of Roman lictors.

Detailed Use of the Rods and Axe by Lictors

The fasces, carried by lictors, functioned as a dual-purpose symbol of magistrates’ authority and as a practical tool for enforcing law and maintaining discipline. Each component, the rods and the axe, had specific, tangible applications in Ancient Rome that reinforced the magistrates’ imperium. Below is a detailed examination of their use, supported by examples from the book.

The Rods: Corporal Punishment

The rods in the fasces were used for public beatings, a method of corporal punishment authorized by magistrates to enforce discipline or deter disobedience. The lictors, acting on the magistrate’s direct orders, carried out these punishments in full view of the public, reinforcing the authority of Roman officials and the consequences of violating societal norms.

Examples from the Republic

Punishment of Soldiers - The rods were often used to discipline soldiers for offenses such as insubordination, desertion, or failure to follow commands. During military campaigns, generals exercised imperium over their troops, with lictors administering beatings as a means of maintaining order. The swift and public nature of these punishments emphasized the seriousness of the offense and served as a warning to others.

Punishment in Public Assemblies - In urban contexts, magistrates used the rods to enforce decorum during public gatherings. Citizens who disrupted assemblies or disrespected officials could be ordered to receive corporal punishment on the spot. The lictors, standing by with the fasces, delivered the punishment as a visible demonstration of the magistrate’s authority.

Judicial Enforcement - Magistrates presiding over legal proceedings used the rods to carry out sentences for minor offenses. For instance, during the early Republic, lictors enforced penalties for crimes such as theft or public disturbances, ensuring that justice was immediate and visible.

The Axe: Capital Punishment

The axe embedded in the fasces symbolized the magistrate’s power to impose capital punishment. This authority was primarily exercised outside the city of Rome, where the axe remained part of the fasces to emphasize the magistrate’s unchecked imperium. The act of execution served not only as a punishment but also as a demonstration of the state’s power to protect its stability and enforce its laws.

Examples from the Republic and Empire

The Execution of Brutus’ Sons - Lucius Junius Brutus, the first consul of the Roman Republic, used the fasces’ authority in a defining moment of Roman history. When his sons conspired to restore the monarchy, Brutus ordered their execution without hesitation. The lictors, carrying fasces with the axe, performed the executions publicly. This act underscored the impartial application of justice under Republican principles, even at the cost of personal loss.

Military Executions - In military contexts, the axe was a constant reminder of the general’s power over life and death. Generals used this authority to maintain discipline and deter rebellion among their troops. Soldiers accused of desertion or treason were executed on the general’s orders, with the lictors acting as enforcers. This served to instill fear and maintain order within the ranks.

Provincial Governance - In Roman provinces, governors wielded the fasces with the axe intact to signify their absolute authority over non-citizen populations. The lack of appeal rights for provincials allowed governors to use capital punishment freely as a tool for maintaining control. Executions carried out by lictors in these regions emphasized Roman dominance and the inviolability of Roman law.

Symbolic Limitation Within Rome - While the axe was a powerful symbol of imperium, its removal within the city of Rome demonstrated respect for the citizens’ rights. Roman citizens had the right to appeal a magistrate’s decision to the assembly or the Senate, a principle known as provocatio. The absence of the axe within the city limits served as a reminder of these legal protections and the balance between magisterial authority and civic rights.

Ritualistic Use and Symbolism

Beyond their practical applications, the rods and axe in the fasces held ceremonial and symbolic significance.

Processions and Public Displays - In triumphal processions or state funerals, the lictors’ fasces represented the magistrate’s authority to enforce order and protect the state. During funerals, the fasces were reversed to signify the end of the deceased’s imperium, emphasizing the temporary nature of power and its limits in the face of death.

Religious Contexts - In some religious ceremonies, the fasces with both rods and axe intact symbolized divine sanction for magisterial authority. By incorporating the fasces into these events, Romans reinforced the sacred legitimacy of their laws and institutions.

Social Implications and Literary Reflections

The use of the rods and axe by lictors had a profound impact on Roman society, shaping perceptions of justice and authority.

Public Fear and Respect - The lictors’ role as enforcers of magisterial orders made them figures of fear and respect. Their presence was a constant reminder of the state’s ability to punish, fostering compliance among the populace.

Critiques by Cicero - In his speeches, Cicero referenced the rods and axe as instruments of justice and tyranny. He praised their role in upholding order but condemned their misuse by corrupt officials like Gaius Verres, who exploited his authority for personal gain. Cicero’s critiques illustrate the dual nature of the fasces as a tool for justice and oppression, depending on the character of the magistrate.

FAQ

Q: What is the fasces, and what does it represent? The fasces is a symbol originating in ancient Rome, consisting of a bundle of wooden rods bound together, typically with a single-headed axe protruding from it. It represented authority, unity, and power. It symbolized the imperium—supreme civil and military power—held by magistrates, and was carried by lictors as a sign of their ability to administer corporal or capital punishment. In modern times, the fasces became a symbol of authoritarianism and was prominently adopted by Italian Fascism.

Q: What are the origins of the fasces, and how did they influence Roman tradition? The fasces likely originated from Etruscan culture, where it served as an emblem of magisterial power. Archaeological discoveries, such as the “Tomb of the Lictor” at Vetulonia, provide evidence of its use as early as 630-625 BCE. The fasces was later incorporated into Roman culture, symbolizing the absolute authority of Rome’s kings and the continuity of power in its Republic.

Q: How did the fasces function in Ancient Rome’s monarchy? During Rome’s monarchy, the fasces symbolized the unlimited imperium of kings, representing their ability to govern and administer justice. Lictors, citizens chosen for this role, carried the fasces in ceremonial processions, emphasizing both the king’s dominance and his preparedness to enforce obedience through coercion. The Etruscan kings, particularly Tarquinius Priscus, were credited with introducing the fasces to Rome.

Q: How did the fasces change with the establishment of the Roman Republic? With the abolition of the monarchy in 509 BCE, the fasces became a symbol of the consuls, who held imperium on an alternating basis. Early consuls, such as Publicola, introduced reforms to democratize its use, including removing the axe from fasces within city limits and lowering the fasces before the people to symbolize their sovereignty. This transition marked the fasces as a tool of Republican governance rather than regal authority.

Q: Who were the lictors, and what roles did they play? Lictors were attendants responsible for carrying the fasces and enforcing the authority of magistrates. They symbolized the magistrates’ power to punish and were viewed as both awe-inspiring and feared. Lictors’ duties included protecting their magistrate, clearing paths, and executing corporal and capital punishment, often using the rods and axe from the fasces.

Q: What is the significance of the fasces in Roman Republican governance? The fasces remained a potent symbol of imperium in the Republic, used by consuls, praetors, and other magistrates. They symbolized both the power and the responsibilities of officeholders. Over time, their use expanded to priests and other officials, demonstrating the adaptability of the fasces as a symbol of Roman authority. The association of the fasces with rotation and equality among consuls also reinforced Republican ideals.

Q: How did the fasces evolve in later Roman and Byzantine periods? The fasces continued to symbolize power in the Roman Empire, though its usage became more ceremonial. The presence of fasces-bearing lictors persisted in municipal governance and even among some priesthoods. In the Byzantine Empire, the fasces remained as a vestigial emblem, used by emperors’ attendants to clear paths. By the fall of the empire in 1453, the fasces had largely faded from active use.

Q: What role did the fasces play during the Renaissance and early modern period? During the Renaissance, scholars rediscovered the fasces through classical texts and art. It became a symbol of unity and strength, linked to Aesop’s fable “The Bundle of Sticks.” This association diverged from the fasces’ Roman origins, emphasizing concord rather than coercion. Artists and writers reinterpreted the fasces as a representation of collective power, influencing its adoption in later political contexts.

Q: How did the fasces become a political symbol in the modern era? The fasces gained prominence in revolutionary France and the United States as a symbol of unity and legitimate authority. In the United States, it appeared in government buildings and symbols like the Mace of the House of Representatives. The fasces’ incorporation into these democratic contexts starkly contrasts with its later use by Mussolini’s Fascist regime in Italy.

Q: How did Mussolini and Fascist Italy reinterpret the fasces? Mussolini appropriated the fasces as the emblem of his Fascist Party, associating it with authoritarian unity and national strength. The regime conducted extensive research to establish an “authentic” Roman appearance for the fasces, which became the national emblem in 1926. Mussolini’s use of the fasces disregarded its historical associations with shared power, instead emphasizing absolute control.

Q: What efforts have been made to dissociate the fasces from its fascist connotations? After the fall of Mussolini’s regime, there were efforts to remove or recontextualize fasces imagery, particularly in Italy. However, in countries like the United States, where the fasces had a broader symbolic history, its use continued in architectural and governmental contexts. Contemporary interpretations often depend on context, distinguishing its ancient and democratic symbolism from its fascist associations.

Q: What contributions does this book make to the study of the fasces? The book provides the first comprehensive synthesis of the fasces’ history, tracing its evolution from ancient Rome to its modern reinterpretations. It emphasizes the layered meanings of the symbol and offers insights into how historical emblems can be co-opted and redefined.

People

Lucius Junius Brutus - Lucius Junius Brutus is celebrated as a founder of the Roman Republic and the first consul to wield the fasces as a Republican symbol of imperium. His execution of his sons for conspiring to restore the monarchy remains a defining moment in the fasces’ history, demonstrating its role in prioritizing public interest over familial loyalty. This act underscored the Republic’s commitment to collective governance, free from regal tyranny. His legacy became a touchstone for later Republican ideals and iconography.

Publius Valerius Publicola - As a key figure in the early Republic, Publicola reshaped the symbolism of the fasces to align with the ideals of liberty and the sovereignty of the Roman people. His reforms included removing the axe from the fasces within city limits to respect citizens’ rights and lowering the fasces in assemblies as a gesture of deference to the people. These measures tempered the authoritarian connotations of the fasces, establishing it as a marker of Republican governance rather than regal dominance.

Tarquinius Priscus - Tarquinius Priscus, Rome’s fifth king, played a pivotal role in introducing the fasces to Rome, borrowing the symbol from Etruscan culture. His reign is closely associated with the establishment of monarchical symbols that underscored the king’s absolute power. The fasces under his rule served as an emblem of regal imperium, demonstrating his authority over both civil and military matters.

Servius Tullius - Servius Tullius, Rome’s sixth king, relied on the ceremonial and coercive power of the fasces to solidify his authority. His reign marked a continuation of the Etruscan influence on Roman governance and highlighted the fasces as a tool for maintaining social order and asserting the legitimacy of the monarchy during contentious transitions of power. (Pages 14-15)

Lucius Tarquinius Superbus - The seventh and final king of Rome, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, epitomized the misuse of regal authority. His tyrannical reign and eventual expulsion led to the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Republic. While his ousting marked the end of royal rule, the fasces transitioned into a Republican context, retaining its symbolic significance as a marker of imperium under consular leadership.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus - This Greek historian of the late first century BCE provides critical insights into the origins of the fasces, emphasizing their Etruscan roots. His accounts link the fasces to the broader cultural and political practices of early Rome, highlighting their role as symbols of authority and continuity from the monarchy to the Republic. Dionysius also explored the symbolic significance of the twelve fasces under Etruscan kings and their subsequent adaptation by Roman consuls.

Marcus Iunius Brutus (the Younger) - A descendant of Lucius Junius Brutus, Marcus Iunius Brutus used imagery of the fasces to emphasize his lineage’s association with Republican values. His coinage, which depicted Lucius Junius Brutus alongside fasces-bearing lictors, symbolized the enduring link between the fasces and the ideals of liberty and justice. These coins served as political propaganda during a time of civil unrest, reinforcing his family’s claim to Republican legitimacy.

Benito Mussolini - As the leader of Fascist Italy, Mussolini redefined the fasces, transforming it into the emblem of the Fascist Party. He appropriated the symbol to represent unity, strength, and authoritarian control, contrasting sharply with its earlier associations with shared Republican governance. Mussolini’s regime conducted extensive research to recreate an “authentic” Roman fasces, elevating it to the status of a national emblem in 1926. This reinterpretation heavily influenced the global perception of the fasces in the 20th century.

Cicero - Cicero, one of Rome’s most prominent statesmen and orators, frequently referenced the fasces in his writings and speeches. He viewed the fasces as a symbol of both magistrates’ power and their accountability to the people. Cicero’s critiques of corrupt officials, such as Gaius Verres, highlighted the expectations placed on those wielding the fasces, emphasizing their role in upholding justice rather than pursuing personal gain.

Marcus Tullius Valgius Rufus - A scholar and contemporary of Cicero, Valgius Rufus provided a linguistic analysis of the term “lictor,” arguing that it derived from their role in binding individuals for punishment. This interpretation underscores the practical and coercive aspects of the fasces as a tool of enforcement, aligning with its broader symbolism of authority.

Plutarch - The Greek biographer and essayist Plutarch offers detailed accounts of key Roman figures and institutions, including the fasces. His writings often humanized the fasces’ history, presenting stories like Brutus’ execution of his sons to illustrate the tension between personal sacrifice and public duty. Plutarch’s exploration of the fasces contributes to our understanding of its role in shaping Roman identity and governance.

Gaius Verres - An ex-magistrate of Sicily, Gaius Verres was famously prosecuted by Cicero for his abuses of power. His misuse of the fasces as a tool for personal gain, rather than justice, serves as a cautionary tale about the responsibilities that come with imperium. Cicero’s speeches against Verres offer valuable insights into the expectations surrounding the fasces and their symbolic weight in Roman society.

Valerius Maximus - A historian of the early Imperial period, Valerius Maximus recorded anecdotes illustrating the importance of the fasces in Roman culture. His works emphasized the symbolic and practical measures introduced by early Republican leaders like Publicola to ensure the fasces reflected the will of the people.

Organizations

The Etruscan League of Twelve Cities - The Etruscan League, a coalition of twelve city-states in central Italy, is credited as the source of the fasces. The League used the fasces as a symbol of unified authority, with each city contributing one lictor when a leader was appointed for joint military campaigns. This practice influenced the Roman adoption of the fasces, first under the monarchy and later in the Republic.

Roman Monarchy - During the monarchy, the fasces symbolized the absolute power of Rome’s kings. The royal institution adopted the fasces from Etruscan traditions, using it to signify the king’s imperium—both civil and military authority. The fasces, carried by lictors, marked the king’s presence and ability to enforce justice and order.

The Roman Republic - The establishment of the Republic saw the fasces transition from monarchical to consular authority. The Republic adapted the fasces to reflect shared governance, with each consul holding the fasces in alternating months. This period also introduced reforms, such as Publicola’s removal of the axe within city limits, symbolizing the people’s rights.

The Roman Senate - While not an organization wielding the fasces directly, the Senate played a crucial role in granting imperium to magistrates who used the fasces. It was instrumental in regulating the powers associated with the fasces, ensuring they aligned with the principles of Republican governance.

The Roman Army - The fasces symbolized military authority in addition to civil power. Generals and consuls carried the fasces during military campaigns to enforce discipline and maintain order. The axe within the fasces emphasized their ability to impose capital punishment in the field.

Fascist Party (Partito Nazionale Fascista) - Founded by Benito Mussolini, the Fascist Party appropriated the fasces as its central symbol, linking it to ideals of unity, strength, and authoritarian control. The party elevated the fasces to a national emblem in 1926, distorting its historical association with shared power and reinterpreting it as a tool of centralized state authority.

United States Government - In the United States, the fasces became a symbol of legitimate authority and unity. It is prominently featured in government institutions such as the Mace of the House of Representatives and the seal of the National Guard. This usage predates and is separate from its appropriation by Italian Fascism.

French Revolutionary Government - The fasces was adopted as a symbol of unity and liberty during the French Revolution. It appeared on coins, emblems, and other artifacts, representing the collective power of the people. This adoption highlighted the fasces’ potential as a democratic symbol, in stark contrast to its later use by Mussolini.

The Vatican and Renaissance Papacy - During the Renaissance, the fasces appeared in papal imagery as part of broader attempts to align the Church with the authority and legacy of Ancient Rome. Artists and intellectuals of the era rediscovered the fasces through classical texts, reinterpreting it as a symbol of moral and spiritual authority.

Byzantine Imperial Court - In the Byzantine Empire, remnants of Roman traditions were preserved, including the ceremonial use of the fasces. While its practical applications diminished, the fasces persisted as an emblem of imperial dignity, carried by attendants in official processions.

Locations

Rome - Rome is the epicenter of the fasces’ historical significance. During the monarchy, it served as the primary location where the fasces symbolized royal imperium. With the transition to the Republic, Rome became the stage for the fasces’ transformation into a Republican symbol. The city saw critical reforms under figures like Publicola, who reshaped the fasces to reflect shared governance. Throughout Roman history, the fasces were carried by lictors within the city, except when adjusted to symbolize respect for citizens’ rights, such as the removal of the axe.

Vetulonia - Vetulonia, an Etruscan city-state, is considered a key origin point for the fasces. Archaeological findings, including the “Tomb of the Lictor,” provide evidence of the fasces’ early use as a symbol of authority among the Etruscans. Vetulonia’s influence on Roman culture underscores the Etruscan contribution to Rome’s adoption of the fasces.

The Etruscan League - The Etruscan League of Twelve Cities played a significant role in the development and use of the fasces. Each city contributed lictors bearing fasces during collective military campaigns or joint leadership, solidifying the symbol’s association with unity and authority. The League’s practices heavily influenced Rome’s ceremonial and political use of the fasces.

The Roman Forum - As the heart of Roman public and political life, the Forum was a key location for the ceremonial display of the fasces. It was here that magistrates presided over legal and political proceedings, their imperium represented by the fasces carried by lictors. Public assemblies in the Forum frequently witnessed the symbolic lowering of the fasces before the people as a gesture of deference.

The Campus Martius - The Campus Martius, or the Field of Mars, was a critical site for military activities in Rome. During wartime, consuls and generals bearing the fasces gathered troops and conducted mustering ceremonies here. The presence of the fasces emphasized the military imperium held by Roman commanders in the field.

Byzantium (Constantinople) - In the Byzantine Empire, Constantinople carried forward many Roman traditions, including the ceremonial use of the fasces. While its practical applications had diminished, the fasces persisted as a symbol of imperial dignity in official processions and state ceremonies.

Florence - During the Renaissance, Florence emerged as a hub for the revival of classical art and ideas, including the reinterpretation of the fasces. Renaissance artists and scholars in Florence frequently incorporated the fasces into their works, linking it to unity and collective strength as conveyed in classical sources like Aesop’s fables.

Paris - Paris became a focal point for the fasces’ symbolic use during the French Revolution. Revolutionary leaders adopted the fasces as an emblem of liberty and unity, incorporating it into coins, statues, and other revolutionary imagery. The city’s monuments and public spaces prominently displayed the fasces as a symbol of collective power.

Washington, D.C. - In the United States, Washington, D.C., features the fasces prominently in its governmental architecture and symbolism. It appears in the Mace of the House of Representatives, the Lincoln Memorial, and other federal monuments, reflecting the fasces’ association with unity and legitimate authority in a democratic context.

Rome under Mussolini - Mussolini’s Fascist regime transformed Rome into a showcase for the fasces as a modern political symbol. The Fascist Party’s reinterpretation of the fasces appeared throughout the city in architecture, monuments, and public events, emphasizing its association with unity, strength, and authoritarian control. Mussolini used Rome’s historical connection to the fasces to legitimize his regime’s ideological claims.

Timeline

~8th Century BCE: Foundation of Rome - The fasces emerges as a symbol of authority in Etruscan culture, influencing early Roman governance. Etruscan kings, such as Tarquinius Priscus, bring the fasces to Rome, where it becomes a marker of royal imperium.

509 BCE: Establishment of the Roman Republic - The monarchy is abolished, and the Republic is founded. The fasces transition from being a symbol of regal power to representing the shared imperium of the consuls. Reforms by Publicola adjust the fasces’ symbolism to reflect popular sovereignty.

5th-1st Century BCE: Republican Era - The fasces remain central to Roman governance, carried by lictors accompanying magistrates and consuls. The symbol evolves to represent both civil and military authority. Its use becomes standardized in public and military ceremonies.

44 BCE: Assassination of Julius Caesar - Marcus Iunius Brutus, a descendant of Lucius Junius Brutus, uses the fasces in coinage to emphasize his Republican lineage and the ideals of liberty. This period highlights the enduring association of the fasces with Republican values during times of political upheaval.

27 BCE-AD 476: Roman Empire - Under the emperors, the fasces become more ceremonial but retain their significance as symbols of imperium. The number of fasces increases with the emperor’s status, signifying the concentration of power in a single ruler.

AD 1453: Fall of Constantinople - The Byzantine Empire, which had preserved some Roman traditions, including ceremonial fasces, collapses. By this time, the fasces’ practical use had faded, though its symbolic role persisted in state and religious ceremonies.

15th-16th Century: Renaissance Revival - The fasces reemerge as a symbol in Renaissance art and literature. Florence and other centers of classical revival reinterpret the fasces, linking it to ideas of unity and collective strength, inspired by Aesop’s fable, “The Bundle of Sticks.”

1789: French Revolution - The fasces become a prominent symbol of the French Revolution, representing unity and liberty. It appears on revolutionary artifacts, coins, and public monuments as a metaphor for collective power against tyranny.

Late 18th Century: American Republic - The fasces are adopted in the United States as a symbol of unity and legitimate authority. It appears in governmental contexts such as the Mace of the House of Representatives and on federal architecture.

1926: Adoption of the Fasces by Mussolini - Benito Mussolini designates the fasces as the emblem of the Fascist Party. It becomes Italy’s national symbol and is widely used in Fascist propaganda, monuments, and architecture to signify unity, authority, and state control.

1945: Fall of Fascist Italy - The defeat of Mussolini’s regime leads to efforts to dismantle the fasces’ association with Fascism. However, its historical and architectural prominence complicates complete removal, especially in countries where it holds broader symbolic significance.

Contemporary Period - The fasces remains a contested symbol, appearing in various contexts ranging from government buildings in the United States to far-right extremist iconography. The symbol’s layered meanings require careful interpretation to distinguish its ancient, democratic, and authoritarian connotations.

Bibliography

Aesop’s Fables - The fasces is connected to Aesop’s fable, “The Bundle of Sticks,” which illustrates the concept of unity and strength through collective effort. This allegory influenced Renaissance and revolutionary reinterpretations of the fasces as a symbol of unity.

Annales by Tacitus - Tacitus provides accounts of the fasces’ use during the Roman Empire, particularly under emperors who expanded its ceremonial role to reflect the consolidation of imperial power.

Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ Historical Writings - Dionysius offers valuable insights into the Etruscan origins of the fasces and its adoption by early Rome. His descriptions link the symbol to early practices of imperium and ceremonial authority.

Plutarch’s Lives - Plutarch discusses key figures like Lucius Junius Brutus and Publicola, who shaped the symbolic meaning of the fasces during the transition from monarchy to Republic. His narratives humanize the symbol and highlight its moral and political implications.

Valerius Maximus’ Historical Anecdotes - Valerius Maximus provides stories about the early Republic and the reforms introduced to democratize the fasces, such as Publicola’s removal of the axe within city limits.

Coins and Inscriptions from the Late Republic - Roman coinage, particularly those minted by Marcus Iunius Brutus, depicted the fasces to emphasize Republican ideals. These artifacts link the fasces to liberty and the Brutus lineage.

Renaissance Art and Literature - Works from the Renaissance period frequently incorporated the fasces, inspired by classical sources. These reinterpretations connected the fasces to collective strength and civic unity, marking its cultural revival.

French Revolutionary Documents and Artifacts - The fasces appeared in official emblems, coins, and revolutionary monuments during the French Revolution. These materials emphasize its role as a symbol of collective power and liberty.

American Founding Documents and Symbols - The fasces is featured in early American government contexts, including the Mace of the House of Representatives. It represents unity and legitimate authority within a democratic framework.

Fascist Propaganda and Architectural Monuments - Under Mussolini, the fasces became the emblem of the Fascist Party. Extensive research and state-sponsored art projects redefined the fasces as a symbol of authoritarian unity and state control.

Glossary

Fasces - A symbol consisting of a bundle of wooden rods bound together, often with an axe protruding. It originated in Etruscan culture and was adopted by Rome to represent imperium, the supreme civil and military authority of magistrates. Over time, the fasces symbolized unity, power, and justice across different historical contexts.

Imperium - The supreme authority held by Roman magistrates, granting them the power to command, enforce laws, and administer punishment. The fasces served as a visible representation of imperium, especially in both civil and military contexts.

Lictor - An attendant assigned to magistrates who carried the fasces and executed their orders. Lictors played both ceremonial and practical roles, including clearing paths, enforcing justice, and symbolizing the magistrate’s authority.

Publicola (Publius Valerius Publicola) - An early consul of the Roman Republic who redefined the fasces’ symbolism by removing the axe within city limits and lowering the fasces before the people to signify popular sovereignty. His reforms marked a shift toward Republican ideals.

Etruscans - An ancient civilization in central Italy that heavily influenced Roman culture. The Etruscans introduced the fasces to Rome as a symbol of magisterial authority, which was later adopted and adapted by the Romans.

Republican Rome - The period following the fall of the monarchy, characterized by shared governance and the redistribution of authority. During this time, the fasces became a symbol of consular power, alternating between consuls as part of the Republic’s ideals.

Aesop’s Fable of the Bundle of Sticks - A story illustrating the strength of unity compared to individual weakness. The fable influenced Renaissance interpretations of the fasces as a metaphor for collective power and solidarity.

Monarchy of Rome - The early period of Roman history, during which the fasces represented the absolute authority of the kings. It was introduced to Rome from Etruscan culture and remained central to the symbolism of governance.

Mussolini’s Fascist Party - A political movement in 20th-century Italy that appropriated the fasces as its central emblem. Mussolini’s reinterpretation of the fasces emphasized unity, strength, and authoritarian control.

Campus Martius - The Field of Mars in Rome, used for military mustering and ceremonies. Consuls carried fasces during these events to demonstrate their military imperium.

Consuls - The highest elected officials in the Roman Republic, each wielding imperium. The fasces symbolized their authority, alternating monthly between consuls to reflect Republican ideals of shared governance.

Constantinople - The capital of the Byzantine Empire, which preserved Roman traditions, including the ceremonial use of the fasces, long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

French Revolution - A late 18th-century political movement in France that adopted the fasces as a symbol of liberty, equality, and fraternity. The fasces appeared on coins, emblems, and monuments as a representation of collective strength.

American Republic - The political system of the United States, which incorporated the fasces as a symbol of unity and legitimate authority. Examples include its use in the Mace of the House of Representatives and federal architecture.

Vetulonia - An Etruscan city that played a critical role in the origins of the fasces. Archaeological evidence from Vetulonia, such as the “Tomb of the Lictor,” supports the symbol’s early association with authority.

Interesting, however I am not completely convinced as to the evolution of meaning of these symbols. I have grown more suspicious of interpretation of historical events and symbols provided by "experts" whose funding comes from institutions or foundations tied to banking or the world revolutionary movement (e.g., Dr. Terry Brennan, Arnold Toynbee).

It seems like much of the “history and science” we were indoctrinated with at school, explained in popular histories and films were lies or the important connections hidden. It would be interesting to discover the designers of the architecture and the seals and who they worked for. I believe there is a lot of hidden meaning in these, which the vast majority of us are left to interpret based on what is written about them.

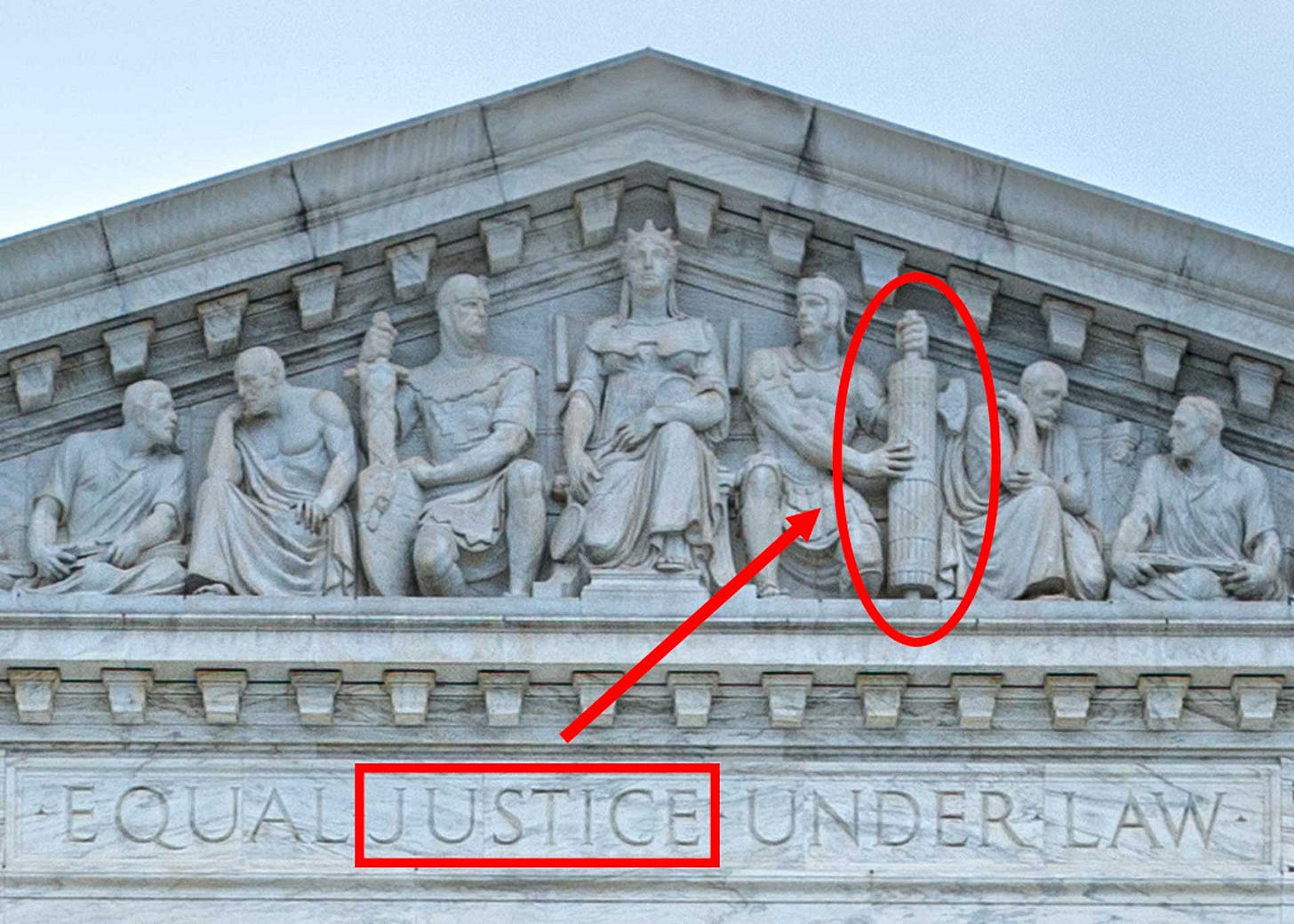

The CO seal (above) has Nil Sine Numine – perhaps means nothing without divinity and then we have the all seeing eye above that, with the ax on the fasces pointed towards it - so which divinity is implied? The use of fasces on the seals for the judiciary seems pretty clear since these branches render judgments (based on laws or not) for the lectors to carry out. Even the military and police forces are seen as being assigned the task of enforcing judgments rendered by their superiors or according to commands - so I can see fasces used in their symbols. Today we have the police with batons (perhaps a modified version of the fasces). However congress does not have enforcement powers. The appearance of these symbols in congress is more than a bit disturbing. Here we see the fasces with the ax pointed towards the flag and the podium. The ax was supposed to be removed in parliament or “sacred” spaces – here it is in full display. The Lectors had high social standing and were very well compensated – well that is true with members of congress – but their compensation does not just come from the citizens/government – it comes from sources outside the government. In antiquity the lictor’s loyalty was solely to the entity they were assigned to protect, otherwise it would have been treason.

I don't think the ancient sculptures ever showed the institution/nobility/ruler which the lictor was to protect - actually touching the fasces. More modern sculptures like Lincoln (above) - suggest that he is the protector (Lictor) of the freed slaves and the union.

I was looking through a coin book, it is interesting to see what the script looked like in colonial times and its progression after the revolution - some interesting changes - but hard to interpret. MA halfpenny 1776 had a lady liberty (perhaps with a cap) sitting on a globe with "Liberty and Virtue" inscribed.

The plans of the House of Rothschild/Jewish Illuminati and its instructions to the Grand Orient Lodges for the World Revolutionary Movement were intercepted by the police/Bavarian Government in 1785 when the courier was struck by lightning. The plans included the design for the French Revolution in 1789 along with other things that have come to pass. Interesting is #10.

Dealing with the use of slogans he said “In ancient times we were the first to put the words ‘Liberty’, ‘Equality’ and ‘Fraternity’ into the mouths of the masses ... words repeated to this day by stupid pollparrots; words which the would-be wise men of the Goyim could make nothing of in their abstractness, and did not note the contradiction of their meaning and inter-relation.” He claimed the words brought under their directions and control ‘legions’ “Who bore our banners with enthusiasm.” He reasoned that there is no place in nature for ‘Equality’, ‘Liberty’ or ‘Fraternity’. He said “On the ruins of the natural and genealogical aristocracy of the Goyim we have set up the aristocracy of MONEY. The qualification for this aristocracy is WEALTH which is dependent upon us.” [From William Guy Carr – Pawns in the Game 1958]

Things probably are not what they seem and I, sure as hell, don’t have the answers. Thanks - Stay Free.

On the Roman connection we recently visited Brindisi in southern Italy and were surprised to find a fountain with the following inscription “ Anno Domini MCMXL / XVIII ab Italia per fasces renovata / Victorio Emmanuele rege et imperatore / Benito Mussolini duce / Provincia f(ieri) f(ecit).”

The meaning of which is “ In the year 1940, the 18th year since Italy’s renovation through the fasces, while Victor Emmanuel III was King and Emperor and Benito Mussolini was Duce, the Province ordered this to be built.”

A commentary and picture can be found at https://flt.hf.uio.no/texts/inscription/269

I’ve lifted a part of the commentary as follows

“The fountain faces the Adriatic Sea and stands at the foot of the steps leading to Piazza Santa Teresa, where the monument to the fallen soldiers of the First World War rises. This location symbolizes both the imperial ambitions of Fascist Italy over the Mediterranean (mare nostrum) and, more subtly, its perceived connection with ancient Rome: Brindisi is the city where the Appian Way ends and from which the Roman army set sail to conquer the East. On the other hand, it also symbolizes the link Fascist ideology forged between the victory in the Great War and the foundation of a new Italian, Fascist empire”.