Thanks to my readers' generosity, all my articles are free to access. Independent journalism, however, requires time and investment. If you found value in this article or any others, please consider sharing or even becoming a paid subscriber, who benefits by joining the conversation in the comments. I want you to know that your support is always gratefully received and will never be forgotten. Please buy me a coffee or as many as you wish.

GPT Book-Summary

Introduction

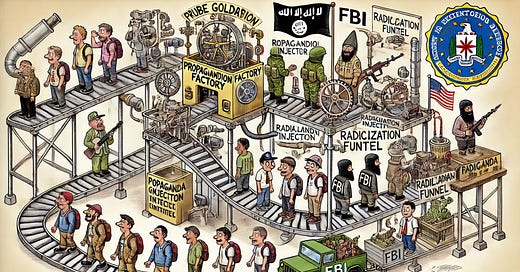

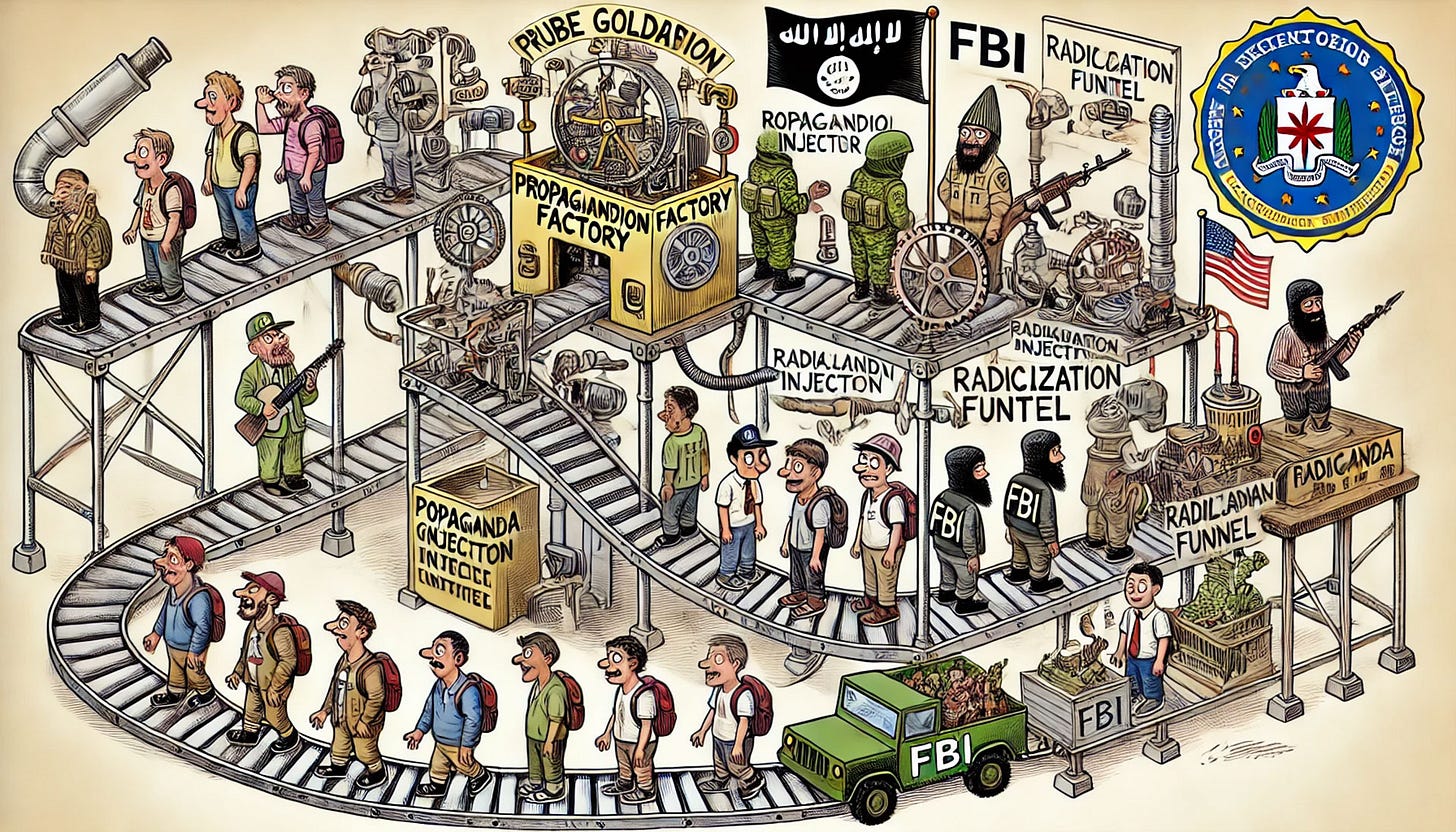

Trevor Aaronson’s The Terror Factory exposes the FBI’s transformation into a counterterrorism force that manufactures plots instead of addressing real threats. Post-9/11 directives from the government mandate preemptive action, leading to the widespread use of informants and sting operations that produce cases with little to no genuine danger. The Bureau targets individuals incapable of committing terrorism without FBI intervention, ensuring convictions through manipulation and entrapment. These operations serve to justify counterterrorism funding while undermining civil liberties.

Summary

📊 Post-9/11 Transformation of the FBI

The FBI becomes an intelligence-driven organization, prioritizing preemptive action over traditional criminal investigation. Counterterrorism becomes the Bureau’s central mission, with policies allowing investigations based on suspicion rather than evidence. The National Security Branch consolidates the FBI’s intelligence and counterterrorism units, enabling large-scale surveillance and sting operations against perceived threats.

Sting operations form the foundation of the FBI’s counterterrorism success. Agents initiate cases by using informants to identify targets, often selecting individuals without means or intent to commit terrorism. Informants offer resources, create plans, and push targets toward criminal activity to fabricate plots that result in high-profile arrests.

🎭 The Role of Informants

Informants play a critical role in nearly every post-9/11 terrorism prosecution. Aaronson reveals that most informants are recruited under duress—often criminals facing prosecution or deportation. These informants are tasked with infiltrating Muslim communities, monitoring places of worship, and identifying vulnerable individuals who can be manipulated into participating in fictitious plots.

Informants drive nearly all FBI terrorism cases. The Bureau recruits informants by exploiting vulnerabilities, offering leniency for crimes or avoiding deportation. Informants infiltrate Muslim communities, monitor mosques, and identify susceptible individuals. Many informants do not merely observe; they actively incite criminal behavior by offering weapons, money, and logistics. These informants fabricate threats, ensuring convictions without actual risk to public safety.

One striking example involves the use of informants who actively encouraged targets to commit acts of terrorism by providing fake weapons, funding, and transportation. These informants do more than gather intelligence—they manufacture crimes that would not have otherwise occurred. Aaronson highlights how many targets lack the intent, means, or capability to carry out attacks without the FBI’s intervention.

🔎 Sting Operations as Manufactured Plots

Sting operations entrap individuals who lack the capacity to execute terrorist attacks independently. The FBI orchestrates these operations by scripting plots, supplying fake explosives, and providing financial support. The Liberty City Seven case exemplifies this tactic. Defendants from a poor Miami neighborhood, manipulated by an informant, are charged with conspiring to bomb the Sears Tower despite lacking weapons, plans, or real intent. This case sets a precedent for future FBI operations, showcasing the Bureau’s focus on fabricating threats to demonstrate success.

💰 Counterterrorism Funding and Public Perception

Counterterrorism funding drives the FBI’s operational priorities. With an annual budget exceeding $3 billion, the Bureau needs a steady stream of high-profile arrests to justify its expenditures. Sting operations guarantee results, allowing the FBI to claim success in preventing terrorism while avoiding scrutiny of its methods. Media coverage reinforces this narrative, amplifying the perceived threat of domestic terrorism and portraying the FBI as a critical defense against it.

🛡 Impact on Civil Liberties

The FBI’s policies erode civil liberties by institutionalizing racial and religious profiling. The Domain Management program targets communities based on demographics, focusing on Muslim populations without evidence of wrongdoing. FBI agents use demographic data to map ethnic neighborhoods, deploying informants to create plots. This approach alienates communities and fosters distrust in law enforcement.

The No-Fly List serves as a coercive tool to recruit informants. Individuals placed on the list without explanation are forced to cooperate with the FBI to regain their right to travel. This tactic exploits legal grey areas, denying due process and undermining constitutional rights. Aaronson highlights this practice as emblematic of the Bureau’s willingness to bypass legal safeguards in pursuit of its goals.

🔨 Key Cases Demonstrating FBI Tactics

Aaronson presents several high-profile cases illustrating the FBI’s approach:

Liberty City Seven (2006) – The FBI orchestrates a plot involving seven men from an impoverished Miami neighborhood. An informant lures them into discussing an attack on the Sears Tower. Despite their inability to carry out the plot without FBI assistance, they are convicted, securing a significant public relations victory for the Bureau.

Antonio Martinez (2011) – Martinez, a young man isolated from society, is coerced into a plot to bomb a military recruitment center. An FBI informant provides fake explosives and encouragement. Martinez’s arrest exemplifies the Bureau’s practice of creating criminals to justify counterterrorism operations.

Najibullah Zazi (2009) – Zazi, unlike most sting targets, represents a real threat. He trains with Al Qaeda and plans to bomb the New York City subway system. Zazi’s case is one of the few genuine successes in FBI counterterrorism, contrasting sharply with the manufactured plots that dominate its operations.

Mohamed Osman Mohamud (2010) – Mohamud, a college student in Portland, Oregon, becomes the target of an FBI sting. An informant pushes him into plotting to bomb a Christmas tree lighting ceremony. Mohamud’s arrest highlights how the FBI identifies and manipulates isolated individuals into becoming criminals.

🧩 Conclusion

Trevor Aaronson’s The Terror Factory presents a searing indictment of the FBI’s post-9/11 counterterrorism strategy. By prioritizing preemptive prosecutions over genuine investigation, the Bureau has created a system where arrests are celebrated over actual public safety. Aaronson argues that this approach not only undermines civil liberties but also diverts resources from addressing real threats.

Through careful research and analysis, Aaronson demonstrates how the FBI’s tactics disproportionately target minority communities, erode trust in law enforcement, and create a false sense of security. The book challenges readers to critically evaluate the ethics and effectiveness of preemptive counterterrorism in modern America.

FAQ

Q: How does the FBI use informants in counterterrorism operations?

The FBI relies heavily on informants to conduct sting operations targeting alleged terrorists. The Bureau employs over 15,000 informants, many of whom are coerced or recruited using leverage, such as threats of deportation or charges for unrelated crimes. These informants do more than observe; they actively create plots by offering weapons, money, and logistics to targets who lack the capability to carry out attacks independently. This approach ensures convictions but raises serious concerns about entrapment and manufactured threats.

Q: What is the FBI’s rationale for terrorism sting operations?

The FBI claims that sting operations are necessary to prevent potential terrorist attacks by preemptively targeting individuals who may radicalize. However, these operations often ensnare economically desperate or mentally unstable individuals, many of whom show no real intent or capability to conduct an attack without the Bureau’s involvement. Critics argue that such operations prioritize fabricated wins over genuine public safety.

Q: How did the FBI shift its strategy after 9/11?

The FBI transitioned from a reactive law enforcement agency to a proactive intelligence-gathering organization. This transformation was driven by directives from the White House and Congress, emphasizing preemption of threats before they materialize. Under new policies like the Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide (DIOG), the Bureau now conducts investigations without needing probable cause, focusing primarily on Muslim communities in the U.S…

Q: What is the role of the Domain Management program?

The Domain Management program enables the FBI to map and monitor specific ethnic and religious communities, particularly Muslim populations, using both government and commercial data. This program facilitates resource allocation and the recruitment of informants. Critics argue that it institutionalizes racial profiling and violates constitutional rights, making it a tool for surveillance rather than legitimate investigation.

Q: How often has the Justice Department prosecuted terrorism cases involving genuine threats?

Analysis of Justice Department data reveals that most post-9/11 terrorism prosecutions involve individuals who lacked any real capacity to commit acts of terrorism. Among more than 500 cases reviewed, only a handful involved actual threats, with most cases resulting from FBI-initiated stings. The majority of these targets had no connection to terrorist organizations until informants provided the necessary means and encouragement.

Q: Why has the FBI focused on lone wolves?

The FBI’s post-9/11 counterterrorism efforts are centered on preventing lone-wolf attacks. These efforts are driven by the belief that the greatest threat comes from isolated individuals who may radicalize independently. However, no evidence supports the Bureau’s assumption that these individuals would meet real terrorists or acquire weapons without FBI intervention. The strategy has led to a disproportionate number of sting operations targeting vulnerable individuals rather than legitimate threats.

Q: What is the ethical concern with FBI informant-driven operations?

FBI informants often act as agent provocateurs, manufacturing plots rather than thwarting genuine threats. Many targets, described by Aaronson as “sad sacks,” are manipulated into participating in plots they lack the means or intention to carry out independently. Legal experts and civil rights advocates have criticized the FBI for creating criminals to secure convictions and justify counterterrorism funding.

Q: How has the FBI justified the expansion of its counterterrorism efforts?

FBI officials, including former directors, have defended the Bureau’s aggressive approach by citing the need to prevent another large-scale attack like 9/11. They argue that sting operations and preemptive investigations are essential tools in identifying potential threats before they act. However, Aaronson’s investigation shows that this strategy has primarily resulted in manufactured plots with minimal public safety benefits.

Q: How does the FBI fund its counterterrorism operations?

The U.S. government allocates approximately $3 billion annually to the FBI for counterterrorism efforts. Despite this significant expenditure, the outcomes have been questionable, with most prosecutions involving low-level offenders ensnared in sting operations rather than genuine terrorists posing imminent threats.

Q: What legislative or judicial oversight exists for FBI counterterrorism operations?

Legislative and judicial oversight of FBI counterterrorism operations is minimal. Although efforts have been made to increase accountability, such as proposed legislation addressing the use of informants, no robust system has been implemented. The Bureau operates with considerable autonomy, raising concerns about unchecked power and potential abuses.

People

Robert Mueller - Robert Mueller directed the FBI during a period of significant transformation following the 9/11 attacks. Under his leadership, the FBI prioritized preemptive intelligence operations over traditional criminal investigations. Mueller’s directive to expand surveillance and intelligence-gathering capabilities allowed for the creation of expansive informant networks targeting minority communities, particularly Muslims.

John O’Neill - John O’Neill led the FBI’s counterterrorism efforts during a time when few recognized the growing threat of Al Qaeda. He was one of the earliest figures to warn of the organization’s capabilities, but his warnings were ignored by senior leadership. His career ended abruptly when he was denied further promotion, and he tragically died in the 9/11 attacks, just weeks after leaving the FBI for a position at the World Trade Center.

Arthur Cummings - Arthur Cummings played a critical role in reshaping the FBI’s domestic counterterrorism strategy. He co-authored the Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide (DIOG), which lowered the threshold for opening investigations and facilitated the surveillance of communities without evidence of criminal activity. Cummings’ work institutionalized practices that critics argue compromise civil liberties.

Dale Watson - Dale Watson, head of the FBI’s counterterrorism section during 9/11, is characterized by his limited understanding of Islamic terrorism. Despite this, he was instrumental in pushing for increased counterterrorism funding and capacity, laying the groundwork for the FBI’s post-9/11 preemptive approach. Watson’s tenure highlighted the Bureau’s ignorance of key cultural and ideological nuances in its early counterterrorism efforts.

Ali Soufan - Ali Soufan, one of the few Arabic-speaking agents in the FBI at the time, was directly involved in counterterrorism investigations before and after 9/11. His language skills and cultural knowledge made him one of the most effective agents in combating Islamic extremist groups, underscoring the Bureau’s general lack of preparedness in this area.

Pat D’Amuro - Pat D’Amuro led the FBI’s counterintelligence and counterterrorism division following 9/11. His leadership was critical in reorganizing the Bureau to handle new threats. D’Amuro’s appointment marked the shift toward intelligence-driven operations, with an emphasis on identifying and preempting lone wolves through expanded surveillance.

Philip Mudd - Philip Mudd, a former CIA analyst, introduced data-driven intelligence models at the FBI, including the controversial Domain Management program. Mudd’s approach focused on demographic mapping of ethnic and religious communities, drawing criticism for racial profiling. His efforts to integrate CIA-style intelligence operations domestically were met with internal resistance from FBI veterans who viewed such practices as unconstitutional.

Organizations

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) - The FBI, once focused on post-crime investigations, has become a preemptive counterterrorism agency since 9/11. This transformation, driven by political pressure and public fear, has resulted in a vast domestic surveillance network targeting Muslim communities. The Bureau employs aggressive sting operations, frequently using informants to manufacture plots and secure convictions. Critics argue that these tactics have little to do with real threats and much more to do with securing funding and demonstrating results.

Justice Department - The Justice Department plays a central role in prosecuting terrorism cases, but the overwhelming majority involve plots orchestrated by FBI informants. Data shows that while few genuine threats have been apprehended, most cases result from manufactured scenarios where vulnerable individuals are lured into fictitious plots. This practice raises concerns about the ethical boundaries of law enforcement and the manipulation of judicial outcomes.

Domain Management Program - The Domain Management program, developed under FBI leadership, uses data analytics to map ethnic and religious communities across the United States. While presented as a tool for resource allocation, it has been criticized for institutionalizing racial profiling by focusing disproportionately on Muslim communities. This program facilitates the recruitment of informants and the initiation of sting operations under the guise of threat prevention.

Al Qaeda - Al Qaeda’s evolution into a decentralized “franchise model” after 9/11 became the justification for many of the FBI’s counterterrorism initiatives. The organization shifted from orchestrating centralized attacks to inspiring lone wolves, a strategy that the FBI claims to combat through preemptive sting operations. However, Aaronson argues that the Bureau often targets individuals incapable of executing attacks independently, making Al Qaeda more of a symbolic justification than an actual threat in many cases.

National Security Branch (NSB) - The National Security Branch, established in 2005, consolidates the FBI’s intelligence, counterintelligence, and counterterrorism efforts. This reorganization allowed the Bureau to increase its surveillance activities and expand its network of informants. The NSB’s focus on preempting threats, rather than investigating crimes, has led to significant controversy over the erosion of civil liberties and the ethics of manufactured plots.

Locations

Liberty City, Miami - Liberty City, an economically disadvantaged area in Miami, served as the backdrop for one of the FBI’s earliest and most controversial post-9/11 sting operations, known as the Liberty City Seven case. The government accused a group of local men of conspiring to blow up the Sears Tower in Chicago, despite lacking evidence that they had the means or genuine intent to carry out an attack. The case, marked by informant-driven entrapment, became a test for the FBI’s strategy of preemptive prosecution. Liberty City’s impoverished environment highlighted how vulnerable communities became targets for FBI stings designed to manufacture terrorism cases.

FBI Academy, Quantico - The FBI Academy at Quantico, Virginia, serves as a training ground where agents learn counterterrorism tactics, including sting operations. In Hogan’s Alley, a simulated town within the academy, agents practice creating and executing scenarios similar to those later used in real-life sting operations. This facility represents the institutional approach to combating terrorism through manufactured plots, an approach criticized for prioritizing convictions over legitimate threat prevention.

Mosques in the United States - Mosques have been heavily targeted by the FBI as part of its Domain Management program. FBI agents, under the guise of community outreach, have infiltrated mosques to gather intelligence on attendees without evidence of criminal activity. This tactic has eroded trust between Muslim communities and law enforcement, reducing the flow of voluntary tips and pushing Muslim Americans to avoid cooperation with federal agents for fear of being targeted themselves.

San Francisco Bay Area - The FBI’s Domain Management program was demonstrated to senior agents using a map of the San Francisco Bay Area, highlighting neighborhoods with a high concentration of Iranian immigrants. This map was used to justify resource allocation and informant recruitment, exemplifying how demographic profiling became central to the FBI’s post-9/11 counterterrorism strategy. Critics argue that this practice mirrors the CIA’s tactics but with troubling implications for civil liberties within U.S. borders.

Timeline

2001: September 11 Attacks - The FBI, under significant pressure from the White House, begins its transformation into a counterintelligence agency aimed at preempting terrorist attacks before they occur. Robert Mueller, newly appointed FBI director, oversees the Bureau’s rapid shift in strategy and operations.

2002–2004: Early Terrorism Stings - The FBI initiates some of its earliest terrorism sting operations, focusing on identifying potential threats from isolated individuals perceived as susceptible to radicalization. Informants are recruited to act as agent provocateurs.

2005: Establishment of the National Security Branch (NSB) - The FBI consolidates its counterterrorism, counterintelligence, and intelligence functions under the newly created NSB. This reorganization further entrenches its focus on intelligence-driven counterterrorism efforts.

2006: Liberty City Seven Case - Federal agents arrest seven men in Liberty City, Miami, accused of conspiring to attack the Sears Tower in Chicago and an FBI office. The men, impoverished and lacking means or intent, are manipulated by an informant into participating in a fictitious plot. Despite initial skepticism, the case becomes a landmark for justifying future sting operations.

2007: Deployment of the Delta Program - The FBI launches Delta, a sophisticated database system designed to manage its growing informant network. Delta allows agents to search and recruit informants based on specific demographic and operational criteria.

2009: Najibullah Zazi Case - Najibullah Zazi, an Afghan American trained by Al Qaeda, comes close to carrying out a bombing on the New York City subway system. Unlike many sting cases, Zazi’s plot represents a genuine threat. The FBI highlights this case to underscore its role in combating real terrorism while critics argue most FBI operations involve fabricated plots.

2010: Expansion of Sting Operations - The Obama administration aggressively supports terrorism sting operations, with Attorney General Eric Holder defending the practice. The FBI increases the frequency of arrests, leading to one high-profile terrorism case every sixty days.

2011: Arrest of Antonio Martinez - Antonio Martinez, a 21-year-old man entrapped by FBI informants, pleads guilty to charges of attempting to use a weapon of mass destruction. His case epitomizes the controversial use of informants to lure vulnerable individuals into committing crimes they would not have initiated independently.

2012: Release of Burson Augustin - Burson Augustin, one of the Liberty City Seven defendants, becomes the first man convicted in a post-9/11 sting operation to be released from prison. His release highlights questions about the legitimacy of convictions secured through preemptive prosecutions.

Bibliography

Jonathan Eig, Get Capone: The Secret Plot That Captured America’s Most Wanted Gangster – Used to draw parallels between historical FBI informant operations and contemporary tactics in counterterrorism.

Ronald J. Ostrow, “Webster Chosen as CIA Director”, Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1987 – Provides context on interagency dynamics between the FBI and CIA.

David Kidwell and Larry Lebowitz, “FBI Sees Terror; Family Sees Good”, Miami Herald, March 31, 2003 – Cited in discussions regarding early sting operations post-9/11.

United States v. Narseal Batiste, FBI Trial Transcripts, 2006 – Central primary source for the Liberty City Seven case, highlighting the Bureau’s entrapment methods.

Lowell Bergman and Oriana Zill de Granados, “The Enemy Within”, PBS Frontline, October 10, 2006 – Explores themes of fabricated terrorism cases and media representation.

Eric Holder, Speech to Muslim Leaders, December 2010 – Quoted regarding the government’s defense of sting operations and the argument that “the ends justify the means”.

Robert S. Mueller III, “Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary”, January 20, 2010 – Used to illustrate how the FBI justifies its counterterrorism strategies before Congress.

Philip Mudd, “Domain Management Strategy Presentation, 2006” – Demonstrates the FBI’s demographic mapping program targeting ethnic and religious communities.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), “Documents on FBI Community Surveillance”, December 2011 – Cited in discussions on FBI overreach and misuse of outreach programs for intelligence purposes.

Amanda Ripley, “Preemptive Terror Trials: Strike Two”, Time, December 13, 2007 – Details on early high-profile sting operations and the public reaction to entrapment cases.

Glossary

Entrapment – Entrapment refers to the practice where law enforcement agents or informants induce a person to commit a crime that they would not have otherwise committed. In the context of terrorism sting operations, FBI informants often play a provocative role, offering targets the means and plans for terrorist acts. Critics argue that these stings fabricate crimes rather than prevent them.

Preemptive Prosecution – Preemptive prosecution is a strategy where individuals are charged based on what they might have done in the future, without waiting for an actual crime to occur. This controversial approach underpins many of the FBI’s terrorism cases, with prosecutors claiming it is necessary to prevent attacks, while defense lawyers argue it criminalizes thought and potential behavior.

Informant – An informant is an individual who secretly provides information to law enforcement about criminal activities. In post-9/11 FBI operations, informants are pivotal in creating sting operations, often coercing or manipulating targets into participating in fictitious plots. The FBI’s extensive informant network has grown to over 15,000, drawing criticism for targeting vulnerable individuals.

Domain Management – Domain Management is a program used by the FBI to map and monitor specific ethnic and religious communities across the United States. It involves demographic profiling and has been criticized for promoting racial and religious discrimination. The program supports the recruitment of informants and the allocation of resources based on perceived community risk.

No-Fly List – The No-Fly List is a government-maintained list of individuals prohibited from boarding flights within, into, or out of the United States. The FBI uses this list as leverage in recruiting informants, particularly within Muslim communities. Despite its original intent to prevent genuine threats, the list has been criticized for including many innocent individuals, leading to legal challenges and public scrutiny.

Lone Wolf – The term lone wolf refers to an individual who acts independently to plan and potentially carry out a terrorist attack without direct connections to a larger organization. The FBI focuses heavily on identifying lone wolves through sting operations, despite limited evidence that such individuals possess the capability to act without external help.

Sting Operation – A sting operation involves law enforcement setting up a scenario to catch someone committing a crime. Post-9/11 FBI sting operations often involve informants who provide fake weapons and encouragement to potential targets, leading critics to question whether the targets would have committed crimes without government involvement.

Agent Provocateur – An agent provocateur is an individual who encourages or incites others to commit crimes, often while acting undercover for law enforcement. In FBI counterterrorism cases, informants frequently play this role, raising ethical concerns about their active involvement in initiating criminal behavior.

DIOG (Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide) – The DIOG is an internal FBI policy document that outlines guidelines for initiating and conducting investigations. It allows for intelligence gathering without requiring probable cause, thus broadening the scope of FBI surveillance activities post-9/11.

Counterterrorism – Counterterrorism refers to the strategies and actions taken by law enforcement and government agencies to prevent and combat terrorism. The FBI’s counterterrorism program involves extensive use of informants, sting operations, and surveillance, with an annual budget exceeding $3 billion.

When America declares "war" on something: poverty, cancer, drugs, terrorism, we seem to experience an exponential rise in said 'enemy'.

Is this Trevor Aaronson playing it dumb, just dumb, or Deep Fake dumb?

FBI mendacity notwithstanding ..The first part of the video shows him presenting a scenario as if the so-called plane hijackers were the cause of the molecular disassociation of the WTC on 911 ..

.. Who is he trying to kid?

www.drjudywood.com